By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 30 March 2017

Anjem Choudary (image source)

The State Department designated five individuals on 30 March 2017 as Specially Designated Global Terrorists (SDGTs), imposing sanctions on them for having “committed, or [for] pos[ing] a significant risk of committing, acts of terrorism that threaten the security of U.S. nationals or the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States.” Four of those sanctioned are members of the Islamic State (IS), including two key British operatives in the group’s global network, and the other is a member of al-Qaeda. On the same day, the Treasury Department sanctioned two IS operatives involved in funding and guiding external IS operations in the Far East and Southeast Asia.

ANJEM CHOUDARY

The most visible person designated as a terrorist yesterday by the State Department was Anjem Choudary, described as “a British extremist with links to convicted terrorists and extremist networks in the UK”.

Choudary came to public attention in the late 1990s as a facilitator for British jihadists heading abroad. Choudary concedes to having made “many mistakes” in his life: while known as “Andy” at Southampton University in the mid-1980s, Choudary was apparently fond of cannabis, alcohol, and womanizing. But, as with many jihadi redemption stories, he found his guide out of sin: Umar Bakri Muhammad, the de facto leader of Hizb-ut-Tahrir in London, an international Islamist organization that argues for military coups as a means of seizing states that can then be governed by Islamic law.

Together, Choudary and Bakri formed al-Muhajiroun. The duo and their loud-mouth outfit would have been laughable—if not for its production of terrorists. One in seven terrorism convictions in the decade after 9/11 led back to Choudary’s organization.

Choudary’s al-Muhajiroun has been linked to: Five of the “Aden Ten” in 1998; Mohammed Bilal, who blew himself in a car outside an Indian barracks in Kashmir on 25 December 2000, making him Britain’s first suicide bomber; Richard Reid, who tried to board a plane with a bomb in his shoes on 22 December 2001; Aftab Manzoor, Afzal Munir, and Yasir Khan, who were killed on 24 October 2001, fighting for the Taliban-Qaeda regime as it went down (all of them from perfectly normal, suburban homes that were “leafy and modestly prosperous”); Asif Muhammad Hanif and Omar Sharif, who blew themselves up at Mike’s Bar in Tel Aviv in April 2003; Michael Adebolajo and Michael Adebowale, who murdered Lee Rigby in May 2013; and Brusthom Ziamani, a Camberwell, south London, native who was convicted in February 2015 for plotting terrorism against British soldiers, among many, many others.

Al-Muhajiroun self-disbanded in October 2004 to avoid a terrorism designation, and Bakri was barred from returning to the United Kingdom a year later when he took a trip to Lebanon. Nonetheless, the British government moved against al-Muhajiroun after the 7 July 2005 massacre on the London subway system by al-Qaeda. The results were very limited. Bakri has acted as an IS recruiter and Choudary has continued to operate al-Muhajiroun, albeit under various different names to avoid the law.

The terrorism menace from Choudary never relented. In 2009, Choudary’s group rebranded as “Islam4UK”. This organization triggered a reaction in Luton that formed the English Defence League (EDL), a far-Right movement. Choudary and the EDL have found a symbiotic relationship as each other’s foes.

Crucially, Islam4UK spawned sister parties throughout Europe, mostly importantly Sharia4Belgium, which sent an early cadre of foreign fighters to the IS movement in Syria when the caliph’s deputy, Samir al-Khlifawi (Haji Bakr), was secretly operating a second track, separate from its formal dependency, Jabhat al-Nusra (since renamed Jabhat Fatah al-Sham and now Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham), in collusion with a small number of locals in and around Aleppo, most importantly Amr al-Absi (Abu al-Atheer). This core laid the groundwork for the creation of a statelet across Syria and Iraq that was declared as a caliphate in June 2014.

As the designation notes, “Choudary was arrested for pledging allegiance to ISIS and for acting as a key figure in ISIS’ recruitment drive” in September 2014. Choudary, who also used the name Abu Luqman, convened with his deputy, Mohammed Mizanur Rahman (Abu Baraa), Siddhartha Dhar (Abu Rumaysa), who moved to Syria in September 2014 to join IS, Simon Keeler, who was later jailed alongside Omar Brooks for terrorism offences, and several others to decide on their allegiance. After a meeting—in a curry house, of all places—in the days after the caliphate declaration, Choudary decided to change his allegiance from al-Qaeda to IS.

On 7 July 2014—seven years today after the massacre on the London transport system by al-Qaeda operatives—Choudary and Rahman were among those who publicly pledged allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Dhar encouraged Choudary to make his allegiance to IS public. Rahman specifically incited Muslims to go to the caliphate.

Choudary had stayed on the right side of the law for twenty years; last year his luck finally ran out, and he and Rahman were convicted on 28 July 2016—revealed 16 August—of inviting support for the Islamic State between 29 June 2014 and 6 March 2015, illegal under section 12 of the Terrorism Act 2000. A 9 September 2014 lecture from Choudary, “How Muslims Assess the Legitimacy of the Caliphate,” was played as evidence. Choudary and Rahman were sentenced on 6 September 2016 to five-and-a-half years in jail. Separately at the Old Bailey on 16 August, Mohammed Alamgir, Yousuf Bashir, and Rajib Khan—all from Luton—were convicted of encouraging others to support IS. All three men were linked to Choudary.

“Choudary has stated that he will continue his recruitment activities from prison,” State notes, and indeed he did. Shortly after Choudary’s conviction and doubtless partly in response, the British government announced plans to keep known jihadists away from other inmates. How successful this is, doubtless time will tell.

EL SHAFEE ELSHEIKH

El Shafee Elsheikh, a British citizen born in Sudan in July 1988, “traveled to Syria in 2012, joined al-Qaeda’s branch in Syria,” the above-mentioned al-Nusra, “and later joined ISIS.”

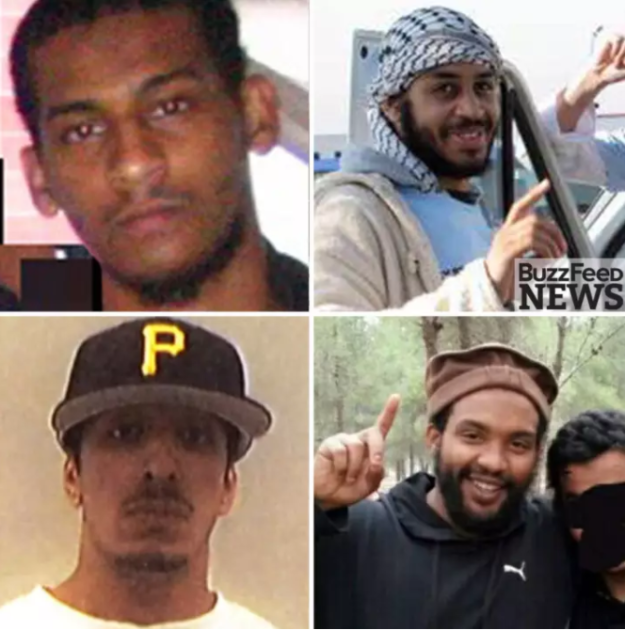

Elsheikh was, as we discovered in May 2016 through a joint Washington Post–BuzzFeed investigation to be, “a member of the [British four-man] ISIS execution cell known as ‘The Beatles,’ a group accused of beheading more than 27 hostages and torturing many more,” as State notes. “Elsheikh was said to have earned a reputation for waterboarding, mock executions, and crucifixions while serving as an ISIS jailer.”

The most famous member of “The Beatles,” a British quartet who guarded foreign hostages, is Mohammed Emwazi (Abu Muharib al-Muhajir), known as “Jihadi John” to much of the English-language media, who was born in Kuwait and made infamous in 2014 after butchering a series of Western captives on video. Emwazi was killed in November 2015 in a drone strike.

The other two members of this foursome are Alexanda Kotey and Aine Davis. Emwazi, Kotey and Davis were all close friends, known collectively as “The London Boys,” gathered around the Manaar Mosque in Ladbroke Grove in west London, getting their start in al-Qaeda networks related to Somalia in the last decade.

Clockwise from top-left: El Shafee Elsheikh, Alexanda Kotey, Aine Davis, and Mohammed Emwazi (source: BuzzFeed)

Kotey is a convert to Islam of Ghanaian and Greek-Cypriot background, whose current location and role with IS is unknown. Davis is a London boy and career criminal, whose father worked for John Lewis, and his membership in IS was disclosed in 2014 when his wife, Aman el-Wahabi, tried to smuggle €20,000 (£16,000) to him in her underwear. Davis was arrested by the Turkish government in November 2015 shortly after the horrific IS attack in Paris, and was allegedly in the process of planning follow-on assaults, charges for which he is currently standing trial (in secret) in Turkey. [UPDATE: Davis was convicted in Turkey on 9 May 2017 of being a senior member of a terrorist organization and sentenced to seven-and-a-half years in prison.]

Elsheikh came to Britain as a child refugee from Sudan around 1993, arriving at age 5. His father left at age 7, and Elsheikh joined the Army Cadet Force, a youth organization, at age 11 and remained there for three years. He went on to become a mechanic in White City, west London.

Elsheikh grew up a short distance from Kotey, Emwazi, and Davis in west London. “Like Kotey, Elsheikh was a football fan who supported the local team, Queens Park Rangers, and he liked to tinker with old bikes and motorcycle engines at a workbench in the family garden,” BuzzFeed reports. “He grew up into a quiet, attentive young man who studied mechanical engineering at Acton College before getting a job at a garage in Shepherd’s Bush and maintaining the rides at the local funfair.”

In 2008, Elsheikh’s eldest brother, Khalid, was jailed for possession of a firearm with intent to endanger—having initially been charged with murdering a rival gang member. Shafee was very close to Khalid, according to his mother, and the separation left him searching for solace and another in-group.

At age 21, circa 2009, Elsheikh “married an Ethiopian woman living in Canada but became frustrated when she was unable to move to London to be with him,” The Washington Post noted, and soon after was drawn into a radical mosque under the sway of Hani al-Sibai, one of the most important pro-al-Qaeda ideologues presently operating. The first sign of this was in 2011 when Elsheikh’s mother, Maha Elgizouli, found him listening to an al-Sibai sermon.

Shafee began dawa (proselytization) work and radicalized his younger brother, Mahmoud, 17. Shafee went to Syria very early, in April 2012, and would be joined by Mahmoud a few months later. Mahmoud was reported killed in March 2015 in Tikrit. On receipt of this news, Ms. Elgizouli tracked down al-Sibai and slapped him in the face, asking: “What have you done to my son?”

Elsheikh would keep in contact with his mother while in the caliphate, including sending pictures of his children, a 2-year-old daughter and 3-month-old son named Mahmoud at the time Elsheikh’s identity was discovered nearly a year ago. “It’s not clear whether Elsheikh is the guard known as ‘Ringo’ or ‘George,’ whom the hostages considered the group’s leader and the most vicious of the four,” according to the Post.

On being told that this is what her son had done, murdering at least seven Westerners and eighteen Syrian soldiers, Ms. Elgizouli said, after the tears, “That boy now is not my son. That is not the son I raised.”

SHANE DOMINIC CRAWFORD

Shane Crawford (source: Dabiq)

Shane Crawford, also known as Abu Sa’d al-Trinidadi and Asadullah, was born in 1986 in Trinidad and Tobago and “is currently believed to be a foreign terrorist fighter in Syria carrying out terrorist activity on behalf of ISIS, including acting as an English language propagandist for the group,” the State Department said.

Crawford’s presence in the ranks of IS was disclosed in October 2014. Crawford had been in Syria since November 2013.

In the fifteenth issue of IS’s English-language magazine, Dabiq, released in July 2016, there was an interview with Crawford, described as “a former Christian who converted to Islam”. Crawford talks through his conversion experience from Baptism, which involves much anti-Christian polemic about it being a religion of polytheism (the Trinity) and idolatry (pictures of Jesus and angels, displays of crucifixes, wearing crosses, and so on). Crawford took inspiration from the July 1990 attempted coup in Trinidad by the radical group Jamaat al-Muslimeen, led by Yasin Abu Bakr. Unsurprisingly, the online lectures of Anwar al-Awlaki were, as they have been for so many others, instrumental in bringing Crawford to jihadism. Al-Awlawi provided a “firmer understanding of what we as Muslims were supposed to be doing,” Crawford explained. Direct contact with an extremist cleric, Ashmead Choate, was also crucial for Crawford. Choate “made hijra [emigration] to the Islamic State and attained martyrdom fighting in Ramadi,” says Crawford.

Crawford says he made hijra to IS-held territory with several others, including another Christian convert named only as “Islam Abu Abdillah,” and “Abu Isa”. Crawford says that while they “awaited [their] opportunity for hijra,” they began to “accumulate money in order to buy weapons and ammo” so that they could “take revenge” whenever “the disbelievers in Trinidad would kill or harm a Muslim”. In this effort at domestic terrorism, “we were successful in many operations,” Crawford claims.

Crawford says that he, Abu Abdillah, and Abu Isa were arrested as part of the dragnet after the attempt to murder the Trinidadian Prime Minister in 2011 led to a state of emergency. But the charges did not stick. Crawford says that it was not in fact true: the efforts of his cell were much more modest. On the eve of leaving to Syria, Crawford and his two close friends delayed the move and instead attended to “some unfinished business with some disbelievers who had wronged the Muslims in the community.” The trio murdered “two kafir (disbelieving) criminals … in the middle of the city in broad day light and was caught on camera,” says Crawford. “It wasn’t our plan for it to occur that way, but it happened according to Allah’s decree.”

The three men and Crawford’s wife met in Venezuela and then made the jump to the Levant. After joining IS, Abu Isa was killed in Marista, near Azaz, when the Syrian rebellion rose against IS in early 2014, and Abu Abdillah was killed in late 2015 while acting as an IS sniper, which apparently is a position occupied by a number of Trinidadian foreign fighters, in the village of Maghribtayn, near the town of Sirrin in Rif Aleppo. Abu Abdillah was killed by “Crusader-backed forces,” says Crawford, presumably referring to the Syrian Democratic Forces, the front-group for the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) that has been the main ground instrument of the anti-IS Coalition.

According to Crawford, about 40% of the Trinidadian contingent within IS are Christian converts. Naturally, Crawford says “many” of the 100,000 Trinidadian Muslims (8% of the population) “are apostates having nothing to do with Islam except its name.” Crawford adds: “When I still was living there, there were Murjiah, modernists, and Tabligh, with a few pockets of pro-Saudi ‘Salafi’ deviants. There are very few people upon the sound creed now, especially as most of them have performed hijra.”

Dabiq noted in its introduction for Crawford’s interview that there were “a large number of muhajirin [foreign fighters] from Trinidad and Tobago fighting under the banner of the Islamic State”. At the time Crawford was identified as being in Syria it was also revealed that about fifty citizens of Trinidad and Tobago had joined jihadi-salafist groups in the Fertile Crescent, including some known figures like Ashmead Mohammed, who was among those arrested on charges of trying to assassinate the Prime Minister, something he strenuously denies.

Perhaps 130 people from Trinidad and Tobago have joined Sunni jihadist groups in Syria, and some politicians in the country think the real number is closer to 400. The country has a population of about 1.3 million. The number of people from the United States who have joined—or even tried to join—IS, al-Qaeda, and others since the Syrian war began came in at just over 250 by the end of 2015. Even if that number had doubled or trebled by now it would underline the point: the U.S. has a population of 320 million (245 times that of Trinidad and Tobago).

Investigating why Trinidad and Tobago is (proportionally) the leading donor of recruits to IS in the Western Hemisphere, Simon Cottee found that there are no easy answer.

There are two versions of Islam on the island, says Cottee, “the Indo Islam of the East Indians, who first came to Trinidad in the mid-19th century as indentured slaves, and there is the Islam of the Jamaat al-Muslimeen, whose members, many of whom were formerly Christians, are almost exclusively black. These two groups do not tend to mix, still less intermarry.” One factor in the radicalization of the island’s Muslim population is believed to be Saudi missionaries disseminating their version of state salafism, known as Wahhabism. Trinidad and Tobago has little economic activity that isn’t driven by its abundant holdings of hydrocarbons, but with the decline of oil prices it has left many adrift. In time of hardship, religious solace is a powerful factor and the Wahhabi proselytizers can be expected to have made advances against this background. Still, as Cottee notes, both of these populations have considerable resistance to this school of Islam. Moreover, the move to the jihadism of IS cannot be accomplished with salafism/Wahhabism alone: it requires a synthesis with the political-revolutionary ideas of Islamism.

Jamaat al-Muslimeen is clearly the more radical of the two Trinidadian Islamic tendencies, and its members have indeed joined IS in (relatively) large numbers, including whole families and one entire community from Diego Martin, a small town north of Port of Spain. But Jamaat al-Muslimeen’s interests are not especially in helping IS recruit. The group engages in mafia-like behavior, smuggling narcotics and weapons, extorting the population, and murdering those who get in their way—and that requires people, as enforcers and to be exploited. As one of Cottee’s sources puts it, “Yasin [Abu Bakr] would never get involved with Islamic State and recruit [people] and send them to Syria, because it’s bad for business!”

Perhaps the only agreed-upon factor in such a heavy flow of recruits to IS from Trinidad is that the government has let it happen: it is not illegal to join IS in Trinidad and no attempt has been made by the state to prevent people migrating to the caliphate. Gary Griffith, Trinidad’s Minister of National Security between September 2013 and February 2015, put it to Cottee this way: “[My] concern as Minster of National Security was not them [the jihadists from T&T] going across [to Syria and Iraq]—they were free to go across, if they wanted—my concern was to ensure that they do not come back.”

MARK JOHN TAYLOR

Mark Taylor (source)

Mark Taylor changed his name to Mohammad Daniel in 2009 and has since taken to calling himself Abu Abdul Rahman. A native of New Zealand, Taylor “has been fighting in Syria with ISIS since the fall of 2014,” according to the State Departmnt. “Taylor has used social media, including appearing in a 2015 ISIS propaganda video, to encourage terrorist attacks in Australia and New Zealand.”

Taylor has been described as the “bumbling jihadi” after a truly stunning breach of operational security in December 2014, when Taylor tweeted out his exact location in a series of posts on Twitter (he was near Tabqa in the Raqqa Province).

A military veteran, Taylor seems to have drifted into Islamism after he was refused the ability to re-enlist in the army. Taylor was arrested in February 2009 in Pakistan as he tried to enter an area occupied by the Taliban and al-Qaeda. That same year, Taylor travelled to meet another Kiwi jihadist in Yemen, Daryl Jones (Muslim Bin John), with whom he had been friends. This jaunt led to Taylor being recommended for travel restrictions. Jones and another jihadi, Australian Christopher Havard, both of whom were radicalised at Christchurch Mosque and then joined al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), were struck down by an American drone in November 2013.

Taylor left New Zealand again in May 2012 and taught English until he entered Syria in June 2014, shortly before the caliphate declaration. By September 2014, however, it seems Taylor was trying to leave: he had allegedly been in contact with the New Zealand government in an attempt to get a new passport, having burned his old one on video upon entering IS-held territory—a standard procedure.

The last time Taylor appeared in the news was as a piece of tabloid fodder when he updated his LinkedIn profile to account for his experience teaching English to children in the caliphate.

SAMI BOURAS

State designated Sami Bouras, a Swedish citizen of Tunisian origins, for being “a member” of al-Qaeda “involved with planning suicide attacks.”

Bouras’ case was highly controversial when he was convicted in June 2004, alongside twelve other young people,1 mostly from the area of Ariana near Tunis, by the Tunisian authorities. Human Rights Watch (HRW) included the case in a report about online censorship in the Middle East and North Africa.

The Ariana case echoed one from several months earlier in Zarzis, which got more attention, where a group of six youths2 had been convicted of using the internet to learn how to create explosives as a prelude to terrorist attacks against a girls’ school and a police station.

HRW noted that the defense teams in both Ariana and Zarzis claimed that their clients were convicted on flimsy evidence from unreliable informants and that the men had been tortured into making false confessions. It was not denied that these men had an interest in “the resistance” in Iraq, Palestine, and Chechnya; it was simply contended that the websites they had visited were for the purpose of youthful curiosity and in any case no law had been broken.

Bouras sentence was up to sixteen years in prison, later reduced to ten years, and ten years of administrative control. It appears Bouras is now in Syria, though details are few.

THE ISLAMIC STATE GUIDES

The Treasury sanctioned Muhammad Bahrun Naim Anggih Tamtomo and Muhammad Wanndy Bin Mohamed Jedi. More commonly known as Bahrun Naim and Muhammad Wanndy, they are the main guides for IS’s foreign intelligence service, Amn al-Kharji, in Indonesia and Malaysia, respectively, as was written about here many months ago. Last week, a report produced for The Henry Jackson Society specifies which of IS’s foreign attacks these men were involved in.

“Naim is a Syria-based Indonesian national and ISIS official who has served in a variety of roles including leading an ISIS unit, recruiting, and overseeing and funding ISIS operations in Indonesia and elsewhere,” Treasury writes. “Naim declared his allegiance to ISIS in August 2014 and as of January 2016 had recruited more than 100 Indonesians for ISIS. As of February 2016, Naim served as one of the leaders of an Indonesian- and Malay-speaking ISIS faction in Syria. By February 2016, he was promoted to be a high official within ISIS.” Treasury then lists three attacks between 2015 and 2016 that Naim not only ordered inside Indonesia but provided the financial resources for.

“Wanndy is a Syria- and Iraq-based Malaysian ISIS operative,” Treasury clarifies, “who coordinates attack planning for ISIS and recruits and facilitates the travel of extremists to Syria to fight for ISIS.” Treasury adds that “Wanndy has directed multiple attacks and provided material support to ISIS,” including attacks in March and June 2016. In this same time period, Wanndy recruited at least three Malaysians and facilitated their travel to the caliphate; they were deported from Turkey and arrested in Malaysia.

* * * *

Notes

[1] The others convicted alongside Bouras were: Hichem Saadi, Anis Hedhili, Riadh Laouati, Kamel Ben Rejeb, Kabil Naceri, Mohammed Ayari, Ahmed Kasri, Ali Kalaï, Bilal Beldi, Hassen Mraïdi, Sabri Ounaïess, and Mohamed Oualid Ennaifer (in absentia),

[2] The Zarziz six were Omar Farouk Chalendi, Hamza Mahrouk, Omar Rached, Ridha Brahim, Abdelghaffar Guiza, and Aymen M’charek

Originally published at The Henry Jackson Society

Pingback: Don’t Assume the Westminster Terrorist is a ‘Lone Wolf’ | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The End of the Line for “The Beatles” of the Islamic State | The Syrian Intifada