By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on October 18, 2015

In the 1990s, the combination of the sanctions and Saddam Hussein’s predatory regime debauched Iraq, ushering in a period of chaos, scarcity, and corruption as the regime gradually broke down. With a religious revival already underway, the population turned to faith for succour, and the regime encouraged this in a way that—in the wake of the brutal repression of the Shi’a rebellion after the first part of the Gulf War—hardened sectarian identities. The security services were deeply affected by the Saddam regime’s Islamization and the Salafists exploited their newfound freedom, and the regime’s increasing lack of capacity, to plot a future after Saddam. By 2003, these various organized Islamist strains, part in and part out of the regime, stood ready to succeed Saddam and had a more zealous and sectarian population to draw on. Saddam had set the stage for the emergence of something like the Islamic State long before Coalition troops invaded Iraq.

A punishing international embargo was imposed on Iraq after Saddam annexed Kuwait in August 1990 and remained after the annexation was reversed because Saddam refused to verifiably surrender his weapons of mass destruction and meet the other conditions of the ceasefire. The formal economy in Iraq, already reeling from Saddam’s war with the Iranian revolution, collapsed.

In 2002, Hayat Shararah, daughter of a noted Iraqi poet and dissident of the monarchy years, Mohamed Shararah, posthumously published Idha al-Ayyam Aghsaqat (If the Days Darken). Hayat had committed suicide with one of her daughters in Baghdad on August 1, 1997. The book, though presented as a novel, documented the horrific way that a once-modern country descended into hell; on top of the political terror came the new horrors of squalor and hunger. The saving graces drained away; there was no space for culture, for reading, and an already militarized and brutalized society was shorn of what was left of its mercy. Men and women of the professional classes were reduced to begging and prostitution just to eat. The final shreds of dignity remaining to Iraqis were removed. Many turned to the faith as a means of anchor, Shararah writes; for many women that meant adopting the veil.

In her excellent biography of Kamel Sachet Aziz al-Janabi, one of Saddam’s most senior Generals until 1998 and a Salafist, Wendell Steavenson writes of the crisis of confidence, the moral retrenchment, that overcame the whole Arab world in the 1970s and 1980s as the “modern” ideologies—pan-Arabism, Ba’athism, Communism—failed. All that was left standing was religion. In Iraq, this crisis was especially acute:

The nineties were the decade in which the sadness bit into the soul. … For exiles the return was salutary. They knew it would be bad … but then they saw with their own eyes the extent of the collapse—Iraq reduced to the Third World … Rackety generators, lakes of sewage, ragged kids in the streets, mounds of flyblown rubbish … and so many women covered in black! … [W]here were the old bars and the restaurants they used to go? Where was the life?

To evade the sanctions, Saddam set up essentially a criminal network, directed by his deputy, Izzat Ibrahim ad-Douri, which smuggled everything from oil to cars across Iraq’s borders. The proceeds from this grey economy were used to pay for a patronage network, often distributed through mosques, of tribes and security services, intended to secure the regime in power. The most heavily subsidized military units were increasingly Saddam’s private militias like the Fedayeen Saddam—loyal to the dictator, not to the country.

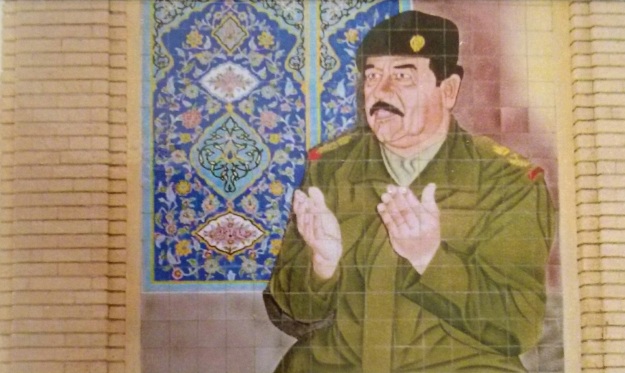

To shore-up further support, Saddam formalized the already-nascent Islamization of his regime by beginning the Faith Campaign in June 1993, also overseen by Douri. Saddam would try to harness the religious revival that had been underway in Iraq since the late 1970s to the legitimacy of his regime by essentially creating a religious trend under his leadership. Call it “Ba’athi-Salafism”.

In this way did Saddam prepare the ideological and material ground for the Islamic State.

Sectarianism had made an appearance during Saddam’s war with the Iranian revolution, and sectarian identities hardened further because of Saddam’s unmerciful repression of the Shi’a revolt in March 1991. Subsequent policies, including the regime narrowing to a Sunni-clan base and treating all Shi’ites as potential subversives, plus inequalities in the Faith Campaign that provided much more leniency for Sunni dissidents and more resources for Sunni mosques, compounded this problem and added an anti-Sunni edge to the Iraqi Shi’a identity.

However cynically the Faith Campaign had started, the system it put in place was very real; mosques and religious leaders became the societal centres of gravity. Many Iraqi Sunnis’ identity now encompassed a strong religious element, and heavy sectarian overtones became staples of identity in all parts of Iraq.

Alongside the Ba’athist-Salafists, the “pure” Salafist Trend had become a potent force. Many Sunnis slipped from Ba’athi-Salafism into “pure” Salafism. With their newfound freedoms, plus the space involuntarily granted by a crumbling regime, the Salafist underground was in a prime position when the regime was overthrown.

Both the Saddamist-Salafists and the Salafi Trend benefited enormously from the chaos and corruption sown by the regime. Douri’s economy stabilized the regime to a degree, giving it some levers of societal control to resist any renewed insurrection, but whereas the Saddam regime of the 1970s and 1980s had been full-bore totalitarian and thus relatively uncorrupt, the regime of the 1990s was criminal. Local strongmen and networks (often tribal) had the run of the country—always with official regime sanction but with the question of who was coercing whom was left rather open. The Salafists offered a governing program that they said would put the world right.

Saddam’s recklessness brought Iraq to crisis and Saddam offered joy in the hereafter as recompense; in a time of national trauma many Iraqis were willing to accept the offer. Saddam had destroyed all opposition except the Islamists, with whom he now aligned. The old middle-class, the social elite that was the repository of a secular, non-sectarian national identity, was devastated and replaced by a clerical elite. Even the younger cadres of the Ba’ath Party, able to sense which way the dictator was tilting if nothing else, adopted a version of Islamism. In the humiliated, broken country of the Saddam-plus-sanctions regime the Salafists promised solace and restored glory in a language whose terms were familiar, unlike the discredited secular ideologies of the 1950s and 1960s. By 2003, the Saddam regime was giving way and some kind of Salafism was going to be the successor force because Saddam had made it so—long before the Anglo-American invasion.

Pingback: Kamel Sachet and Islamism in Saddam’s Security Forces | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The foundations of ISIS: How secular tyranny fostered religious zealotry in the Middle East

Pingback: The Riddle of Haji Bakr | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Islamic State Was Coming Without the Invasion of Iraq | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: How the Islamic State’s Caliph Responded to Defeat Last Time | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Mosul Operation and Saddam’s Long Shadow | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: America Sanctions Anjem Choudary and other British Islamic State Jihadists | The Syrian Intifada