By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 9 February 2018

El Shafee Elsheikh (image source) and Alexanda Kotey (image source)

Last night, The New York Times reported and Reuters confirmed that two British Islamic State (IS) jihadists, El Shafee Elsheikh and Alexanda Kotey, both of them designated terrorists by the United States, have been arrested in Syria. Kotey and Elsheikh, along with the late Mohammed Emwazi (Abu Muharib al-Muhajir) and Aine Davis, formed a four-man cell that has become known as “The Beatles”—hence Emwazi being near-universally known as “Jihadi John”—that guarded, abused, and murdered hostages for IS from before the “caliphate” was founded in 2014.

EL SHAFEE ELSHEIKH

The most extensive information about Elsheikh is known from a joint Washington Post–BuzzFeed investigation published in May 2016 when it was revealed that Elsheikh was the fourth “Beatle”.

Elsheikh was born in Sudan on 16 July 1988. The next year, Islamists swept to power in Sudan, intensifying the country’s long-running civil war, and Elsheikh’s parents, members of the Sudanese Communist Party, fled to Britain in 1993. Elsheikh is now a British citizen.

Elsheikh grew up in West London. While this is the same area of London where the other “Beatles” lived, it seems Elsheikh was a late-comer to the group. Part of this is physical distance: Elsheikh lived in White City, which was a few miles away from the other three. And it is known that Emwazi, Kotey, and Davis all grew up together as friends; their association with Elsheikh is not evident until around 2012. Indeed it is unclear if Elsheikh knew the others before they departed to Syria. For example, while Emwazi and Kotey were definitely part of “London Boys” network led by Bilal al-Berjawi (Abu Hafsa), which in the mid-2000s recruited jihadists, primarily for al-Qaeda in Somalia, and Davis probably was, too, there is no evidence Elsheikh was part of the Berjawi set. If the four had met in Britain, the social space will have been Al-Manaar mosque and Muslim Cultural Heritage Centre in the Ladbrokes Grove area in West London, where they were all radicalized by IS recruiters and which has been linked with other terrorism cases.

Elsheikh had been perfectly ordinary into his early teens, supporting Queens Park Rangers football team, joining the Army Cadet Force for three years when he was 11-years-of-age (1999 or 2000), and then working as a mechanic. But as Elsheikh reached his later teens trouble began, including involvement with criminal gangs. A gang member with whom Elsheikh was feuding was killed in 2008, when Elsheikh was around 20-years-old, and Elsheikh’s eldest brother, Khalid, was charged with his murder. Khalid was eventually cleared of murder, but was imprisoned for ten years for illegal possession of a firearm. According to Elsheikh’s mother, Maha Elgizouli, and other close friends, this was a turning point that left Elsheikh more open to jihadist propagandist-recruiters.

At age-21 (c. 2010), Elsheikh “married an Ethiopian woman living in Canada but became frustrated when she was unable to move to London to be with him”, The Post reports. “The following year, the mother said, she started to notice changes in her son after an older friend introduced him to the preaching of a West London imam known for his radical beliefs.” The preacher was Hani al-Sibai (Abu Karim), a prominent pro-al-Qaeda jihadi cleric based in London,[1] whose material Elsheikh’s mother found him listening to in 2011. Elsheikh’s turn to radicalism was apparently sudden, taking place in just under three weeks. This created tensions within the household, including hours-long debates over Islam, one of which ended with Elsheikh saying, “You know, Allah says your mum can be your enemy.” After Elsheikh went to Syria, his mother tracked down al-Sibai and slapped him in the face, asking, “What have you done to my son?”

Elsheikh arrived in Syria in April 2012. Elsheikh’s brother, Mahmoud Elsheikh, joined him in Syria a few months later in 2012. Elgizouli had taken Mahmoud to Sudan to try to get help from the family in dissuading him from following his brother and even confiscated his passport. But the British Embassy issued Mahmoud another passport and jihadi networks in Sudan got Mahmoud a plane to Turkey. Mahmoud was killed fighting for IS in Tikrit, Iraq, in March 2015.

Elsheikh, Emwazi, Davis, and Kotey joined the jihad in Syria early, all apparently becoming part of Jabhat al-Nusra. Al-Nusra was, at that time, a secret branch of IS, breaking away to join al-Qaeda in April 2013, and now reorganised as Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). There are indications, however, that the foursome were members of—or at least closely linked to—the parallel infrastructure that IS had laid down in northern Syria.

Distrustful of their own viceroy, al-Nusra leader Ahmad al-Shara (Abu Muhammad al-Jolani), IS recruited networks that formally remained under al-Nusra’s banner, most importantly in Aleppo gathered around Amr al-Absi (Abu al-Atheer), but which answered directly to the caliph’s deputy, Samir al-Khlifawi (Haji Bakr), rather than al-Shara. This meant that when IS and al-Nusra publicly split, vast numbers of field commanders and most of the foreign fighters, such as Tarkhan Batirashvili (Abu Umar al-Shishani), and virtually the entire infrastructure around Aleppo “defected” from al-Nusra to IS. The Syrian opposition then ejected IS from Aleppo in early 2014. It took al-Nusra many years to re-establish any presence in Aleppo city, and it remained marginal right down to the end in December 2016.

Mohammed Emwazi (source: Al-Naba)

Elsheikh had come into Syria before Emwazi, the duo seem to have been in the same unit all along the way, and Emwazi certainly had connections to al-Absi’s networks. There is also the simple geographic point: IS and al-Absi had not set themselves up in Aleppo by accident. This was the area into which most of the foreign fighters, the most zealous and obedient contingent of IS, flowed, particularly around Jarabulus and especially al-Bab, where IS’s foreign intelligence service, the amn al-kharji, and its leader, Abdelilah Himich (Abu Sulayman al-Firansi), were based. Elsheikh’s cell held hostages in the basement of a hospital in Aleppo until IS was evicted from the city, at which point they took their captives to Raqqa.

Dealing with one of the more frivolous aspects, The Post says: “It’s not clear whether Elsheikh is the guard known as ‘Ringo’ or ‘George,’ whom the hostages considered the group’s leader and the most vicious of the four.” Whichever of the two Elsheikh was, Kotey was the other one. From an online post by “Ringo”—describing himself as “British as they come … born and raised in Shepherd’s Bush, was a big QPR fan, love a good old fry up in the mornings”—it seems Kotey is probably “Ringo”, Elsheikh was “George”, and thus Davis is “Paul”.

More seriously, “Elsheikh was said to have earned a reputation for waterboarding, mock executions, and crucifixions while serving as an ISIS jailer”, according to the State Department sanctions that named Elsheikh as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist (SDGT) in March 2017. “The Beatles” cell was involved in beheading at least twenty-nine people—James Foley, Steven Sotloff, David Haines, Alan Henning, Abdurrahman (Peter) Kassig and twenty-two Syrian soldiers, Haruna Yukawa, and Kenji Goto.

After IS had murdered its hostages and Emwazi had been killed in a drone strike, Elsheikh seems to have moved back west from Raqqa: his mother told The Post in 2016 “that Elsheikh is living in Aleppo with a Syrian wife … and that his Canadian wife has also joined him in the country”. In 2016, Elsheikh had two children: a two-year-old daughter with his Syrian wife, who was named Maha, after his mother; and a three-year-old boy with the Canadian wife, named Mahmoud, after his dead brother. Elsheikh retained contact with his mother, sending her pictures of the children.

ALEXANDA AMON KOTEY

Alexanda Kotey, who took on the kunya Abu Salih al-Britani, was identified as part of “The Beatles” IS cell in February 2016 by BuzzFeed and The Washington Post.

Kotey was born in Paddington in West London on 13 December 1983 to a Ghanian father and Greek-Cypriot mother. His father died on 17 November 1986, apparently committing suicide by jumping in front of a train. Kotey grew up in the Shepherd’s Bush area and “converted to Islam in his early 20s after meeting a Muslim woman with whom he had two children before they separated”, The Post reports. Like Elsheikh, Kotey was an avid QPR fan.

Kotey, known as “Alexe” to his friends, then attended Al-Manaar mosque, and “friends recalled that he stood out for his radical views”, The Post notes. “One former friend said Kotey used ‘to have this stall outside the mosque, and those guys used to openly preach and argue about what they thought was their cause or ideology.’ The friend … said Kotey also advocated suicide bombing, arguing with those who said it was forbidden by the Koran.”

Kotey was involved with al-Qaeda’s “London Boys” network from 2008 at the latest. Emwazi was part of this network from around 2007—perhaps earlier, according to IS. Kotey left Britain in February 2009 as part of the 110-vehicle “Viva Palestina” aide convoy bound for HAMAS-ruled Gaza, and that was the last his family saw of him.

The Viva Palestina convoy, led by George Galloway, has “[a]s many as eight known or suspected extremists” among its 300 or so participants, the London Times reported. These include: Kotey and two other members of the “London Boys”, Amin Addala and Reza Afsharzadegan[2]; Ronald Fiddler (Jamal al-Harith), a Manchester convert and former inmate at Guantanamo who blew himself up while fighting for IS in Mosul in February 2017; Stephen Gray, also from Manchester, a former member of the RAF who tried to join IS; Munir Farooqi, a former Taliban fighter imprisoned in 2011 after trying to recruit undercover officers; and “two other men who cannot be named.”

Kotey was sanctioned as a SDGT by the State Department in January 2017. “Kotey, a British national, is one of four members of an execution cell for … the Islamic State”, State wrote at the time. “As a guard for the cell, Kotey likely engaged in the group’s executions and exceptionally cruel torture methods, including electronic shock and waterboarding.” The U.S. designation made reference to the “notorious cell, dubbed ‘The Beatles’ [that was] once headed by now-deceased SDGT Mohamed Emwazi”. This is somewhat contested.

In its profile of Kotey, BuzzFeed noted that there is evidence that “George” had considerable sway over the cell:

A Danish hostage, Daniel Rye, who was released in June 2014, recalled in a memoir how “Ringo” had kicked him 25 times in his ribs on his 25th birthday, telling him it was a gift. Rye wrote that “George” dominated the group of jailers and was the most violent and unpredictable.

Rye also recalled being taken to an open grave where a suspected spy was shot by Emwazi on “George”’s instructions while “Ringo” filmed. Rye said the Britons forced him and other hostages to climb into the grave and photographed them.

As mentioned above, “George” seems to be Elsheikh and Kotey is “Ringo”.

There are significant gaps in what is known about Kotey, which might perhaps be filled in the days to come. One intriguing thread comes from the State Department designation, which says that “Kotey has also acted as an [IS] recruiter and is responsible for recruiting several UK nationals to join the terrorist organization.” It would be interesting to know the degree to which Kotey was involved in IS’s propaganda-recruitment activities and if that tipped over into any involvement in IS’s guided attacks around the world.

* * * * *

Aine Davis (image source)

The immediate question is whose custody Elsheikh and Kotey will end up in. The pair are currently in a prison controlled by the so-called Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) who have not always proven the most reliable custodians of IS captives, but who know the immense political benefit they will reap from handling this case as Western governments instruct them. The obvious destination for Elsheikh and Kotey is the United Kingdom. However, a U.S. official tells The New York Times that the British government has revoked the citizenship of Elsheikh and Kotey, which, if true, would mean Britain was content for others to deal with this matter. This has proven to be the case with the other “Beatle”, Aine Davis, who is in prison in Turkey. The British state has stripped citizenship from a number of jihadists who joined IS, but it cannot do this if it would leave the individual stateless. Kotey has alternate citizenship; it is not clear Elsheikh does. Both Elsheikh and Kotey are on the U.S. sanctions list, so an attempt by America to take possession of the two men to prosecute them is conceivable. Whether this would be in civilian Federal courts, or under military jurisdiction—President Donald Trump having recently reaffirmed his support for keeping the Guantanamo Bay facility open—is unclear.

There is also the matter of what happened to all the foreign fighters. The estimates are that 40,000 people from 120 countries joined IS, approximately 6,000 of them from Europe. As the caliphate collapsed, European security agencies braced for a flood of trained returnees to create domestic mayhem. Not only has this not materialised, but the foreign fighters have not shown up in theatre, despite the “annihilation tactics”.

In Mosul, IS planned and executed something like a “last stand”. This was an exception. In line with past practice, IS consistently fell back from the cities almost everywhere else, and, after the nine-month campaign to expel IS from Mosul concluded, IS wrapped up very quickly. The Raqqa operation began in June and IS retreated in October; the next month, clearance operations in urban zones along the Euphrates River Valley in Syria were declared complete, and the month after that rural efforts in western Iraq supposedly finished. The bulk of IS’s fighting force survived; the organization wholly reverted to insurgency in October and such tactics had been showing progress, even as the statelet was eroded, months beforehand. This makes the missing fighters all the more puzzling.

Surely some of the most dedicated and important foreign fighters are still in the pockets of caliphal territory around Hajin and al-Bukamal, and many more are waiting out the storm in Turkey thanks to the enterprising human smugglers along Syria’s northern border. Still, the numbers do not add up. There is good reason to think the numbers were inflated to begin with. Perhaps between them these reasons explain what happened. Elsheikh and Kotey seem well-placed to answer this question.

* * * * *

Notes

[1] Another important pro-al-Qaeda cleric in London is Abu Mahmud al-Filistini. Al-Sibai and Abu Mahmud—with Issam al-Barqawi (Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi) and Umar Othman (Abu Qatada al-Filistini) in Jordan, and Tariq Abdelhaleem in Canada—function as ideological pillars, generating legitimacy for the jihadi-Salafist movement.

[2] Afsharzadegan, also known as “Adam”, is of Iranian origin and was first among equals in the “London Boys” network. In late 2006, Afsharzadegan led a delegation of British jihadists—Mohammed Ezzouek, Hamza Chentouf, and Shahajan Janjua—to Somalia, where they trained with Fazul Abdullah Mohammed (Harun Fazul), al-Qaeda’s effective leader in East Africa, according to the leaked Guantanamo file for Abdulmalik Mohammed, a Kenyan jihadist within Fazul’s network. Afsharzadegan was “a close associate” of, and “kept in phone contact with”, Abdulmalik Mohammed, according to the Guantanamo file. Afsharzadegan then returned to London and began recruiting for Harakat al-Shabab al-Mujahideen, al-Qaeda’s Somali branch.

* * * * *

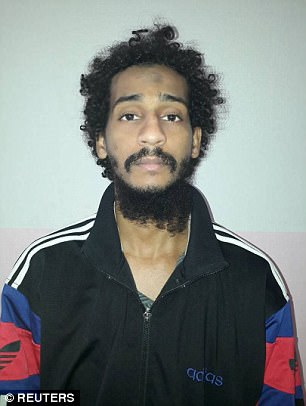

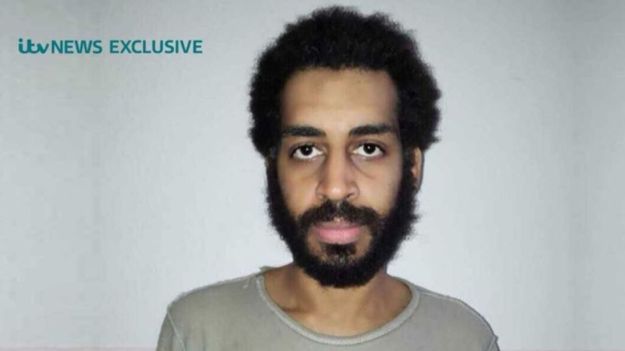

UPDATE: On 9 February 2018, pictures of the two captured “Beatles” were made available by the “SDF” forces.

Alexanda Kotey’s photograph was the first to be released to ITV News:

El Shafee Elsheikh’s photograph was then released: