By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on December 12, 2015

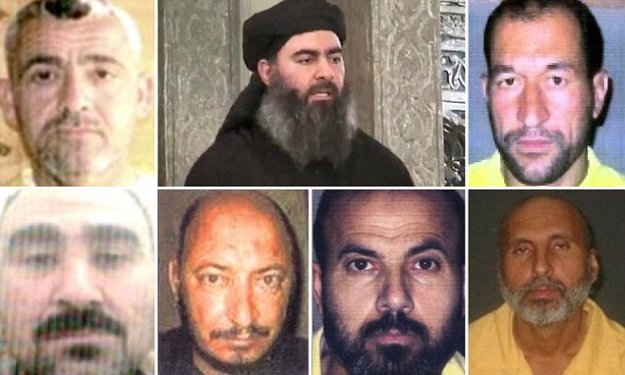

From top left clockwise: Fadel al-Hiyali, Ibrahim al-Badri (Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi), Adnan al-Bilawi, Samir al-Khlifawi (Haji Bakr), Adnan as-Suwaydawi (Abu Ayman al-Iraqi), Hamid az-Zawi (Abu Omar al-Baghdadi), Abu Hajr as-Sufi

Yesterday, Reuters had an article by Isabel Coles and Ned Parker entitled, “How Saddam’s men help Islamic State rule“. The article had a number of interesting points, but in its presentation of the movement of former (Saddam) regime elements (FREs) into the leadership structure of the Islamic State (IS) as a phenomenon of the last few years, it was a step backward: the press had seemed to be recognizing that the Salafization of the FREs within IS dates back to the Islamization of Saddam Hussein’s regime in its last fifteen years, notably in the 1990s after the onset of the Faith Campaign.

The authors do note that when IS swept across Iraq in June 2014 and “absorbed thousands of [Ba’athist] followers,” these “new recruits joined Saddam-era officers who already held key posts in Islamic State” (italics added). But the Reuters piece then adds:

Most former Baathist officers have little in common with Islamic State. Saddam promoted Arab nationalism and secularism for most of his rule. But many of the ex-Baathists working with Islamic State are driven by self preservation and a shared hatred of the Shi’ite-led government in Baghdad. Others are true believers who became radicalised in the early years after Saddam’s ouster, converted on the battlefield or in U.S. military and Iraqi prisons.

The notion of a cleavage in IS between true believers and “Ba’athists” doesn’t stack up in the article’s own presentation. The notorious Camp Bucca where IS deliberately infiltrated men to gather recruits, some of whom were FREs, was important. But the very formulation begs the question. Why were insurgent leaders using Islam, not Ba’athism, as their rallying cry? Why was there “no secular Sunni resistance at all,” as Joel Rayburn, a former intelligence officer who worked with General David Petraeus from 2007 to 2010 and wrote one of the best histories of post-2003 Iraq, once put it? Because Ba’athism had been dead as an ideology for at least a decade—and it was Saddam who killed it.

Saddam Prepares the Ground Ideologically for Islamic State

Saddam had taken extensive steps to Islamize the government and society since the mid-1980s, which profoundly affected the security sector. While this began cynically, the evidence, as extensively documented in Amatzia Baram’s book on the subject, is that Saddam had a conversion experience. But, as Baram points out, even if Saddam remained a cynic, his government acted to promote a religious movement under his leadership—call it Ba’athi-Salafism—and reshaped society by, for example, empowering clerics as social leaders, notably in Sunni Arab areas where they had not been before. Saddam’s conversion and alliance with the “pure” Salafi Trend, which had long been in opposition to the Ba’ath regime but found itself less opposed in the latter years, deeply worried senior regime figures like intelligence chief (and Saddam’s half-brother) Barzan al-Ibrahim, who could see the rise of this religious militancy and predicted that it would eventually supplant the regime.

This is why the word ‘Ba’athist’ is so unhelpful in these discussions: it assumes what people are being asked to prove. It also mixes together two related but distinct streams within the Iraqi insurgency, namely the individual FREs who joined IS as true believers and the FRE-led groups who worked alongside the foreign-led Jama’at at-Tawhid wal-Jihad (JTJ), Abu Musab az-Zarqawi’s group, which would become al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) and eventually IS, while remaining separate entities, many of whom later turned on IS’s predecessor during the Awakening.

Even the more “Ba’athist” sections of the insurgency, however, grouped around Saddam’s former deputy, Izzat ad-Douri, and the Sufi networks he had within the regime and its security apparatus, which eventually unveiled themselves as Jaysh Rijal at-Tariqa an-Naqshabandiya (JRTN), were not secular: Islamism has always been a deeply integral part of JRTN.

And while there was a deep overlap ideologically between the Iraqi Ba’athi-Salafists and the foreign-led jihadi-Salafists connected to al-Qaeda who formed the insurgency after Saddam’s fall, operationally the connection was even deeper—and longer standing.

Saddam’s Contacts With Islamists and Jihadists Predate 2003

The Reuters piece notes: “Baathists began collaborating with al Qaeda … soon after Saddam Hussein was ousted in 2003.” But this isn’t right. The first major official break with the hard-secularism that the Ba’ath regime displayed after it brutalized its way to power in 1968 came in 1986, when Saddam began instrumentalizing Islamists in Iraq’s foreign policy. This would include the Muslim Brotherhood, the Taliban, and eventually al-Qaeda, with which the Saddam regime had a long record of contact dating back to at least 1992.

But put aside the fact that when Osama bin Laden was considering leaving Afghanistan due to tensions with the Taliban in late 1998 and early 1999, it was to Baghdad he was considering moving. Put aside that Saddam’s intelligence agencies colluded in the 2002 bombing by al-Qaeda’s Abu Sayyaf Group that killed Sgt. Mark Wayne Jackson, the only American soldier killed by terrorism in the Philippines. Even leave alone the ever-thorny matter of Ansar al-Islam, through which Saddam and al-Qaeda collaborated in waging war on the Kurdish autonomous government in northern Iraq.

Just look at JTJ/AQI and Zarqawi: When did they arrive on Iraqi soil? April 2002. Zarqawi was then in Baghdad by May, with a dozen senior al-Qaeda members, and a flow of jihadists continued into Baghdad in the summer and fall of 2002, including Zarqawi’s successor, Abu Hamza al-Muhajir. Zarqawi was then able to begin connecting with the militant Salafist underground that had built up under Saddam’s Islamization policies, and begun infiltrating the security apparatus, as well as receiving the first of the foreign fighters, who seem to have had no trouble receiving official visas from Saddam’s state. It was Saddam, ideologically and in his behaviour towards the Zarqawists, who opened the door and provided the crucial start-up help to the men who would form IS.

Zarqawi was the allowed free movement across central Iraq and indeed Iraq’s borders in this period, recruiting individuals such as Aleppo-based Taha Subhi Falaha, better known as Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, IS’s powerful official spokesman, and setting up the “ratlines” through Syria that would bring the foreign fighters to IS’s predecessor. The Assad regime was complicit in Zarqawi’s actions at this time, too, not only in forming the networks that brought the foreign volunteers to IS but the assassination (p. 106) of USAID worker Laurence Foley in Amman by Shaker al-Absi, a known asset of Syrian intelligence. Zarqawi returned to Iraq in October 2002, if not before, and in November 2002 took residence in Ansar al-Islam-controlled territory. Zarqawi and his band of Ansar fighters fled to Iran during the invasion.

Meanwhile, Saddam had emptied the prisons and brought thousands of foreign fighters into Iraq, many through State-directed mosques which were connected to international Islamist networks by ad-Douri, and these fighters, under the command of the heavily-Salafized loyalist militia, the Fedayeen Saddam, were almost the only resistance against the Coalition invasion and a handy recruiting pool for Zarqawi thereafter.

The major phase of “Ba’ath”-Qaeda collaboration that Reuters refers to is when the embryonic alliance took full bloom in the summer of 2003 after Ansar and Zarqawi were infiltrated back into Iraq from Iran with help from ad-Douri. (Ansar would split once back in Iraq, with part joining Zarqawi and the remnant reasserting its autonomy, until formally swearing allegiance to IS in 2014.) Ad-Douri, who used the looted treasury of the fallen regime to direct much of the immediate post-Saddam insurgency, assisted Ansar and JTJ/AQI with access to car bombs and other weapons, plus intelligence and operatives, notably in the three “spectaculars”—against the Jordanian Embassy and the United Nations headquarters in the Canal Hotel in Baghdad, and the mosque of Ayatollah Mohammad Baqir al-Hakim in Najaf—that marked the definitive beginning of the insurgency.

The Ex-Saddamists Were in Islamic State All Along

Reuters records a meeting in June 2014 where “Islamic State told Baathists they had a choice: Join us or stand down.” Some “Ba’athists” did join IS, and this “boosted Islamic State’s firepower and tactical prowess,” according to Reuters. But again, the timeline here doesn’t make sense—even on its own terms. IS was able to present this ultimatum to the “Ba’athists” because IS had already defeated them on the battlefield. The military prowess IS has from the infusion of intellectual property from the fallen Saddam regime was acquired long before the Iraq offensive of 2014.

The reason IS looks different now is because its opponents have changed. Jessica Lewis McFate, who served for eight years as an intelligence officer in the U.S. military and worked in Iraq in 2007 and 2008, explained:

The organization that I encountered … was a disrupted terrorist organization on the run and its tactics involved IEDs to try to counter our obviously superior ground forces. … So that’s really where we saw the group become hyper-specialized in different ways of building different kinds of bombs. …

What we saw in 2012 and 2013 was a resurgence, first, of the same kinds of activities that we used to see, primarily vehicle-borne IEDs, suicide vests, and much greater numbers—demonstrating that their ability to fund and resource operations were coming back online, but the tactics weren’t necessarily different … They had, unfortunately, by the end of 2013 come all the way back to early 2007 levels, so this was basically AQI before the surge, culminating with the Abu Ghraib prison break …

What we saw in the intervening period [between the departure of U.S. troops in December 2011 and] January 2014 when ISIS began to launch attacks into Ramadi and Fallujah … was a build-up in attacks against military targets, but they weren’t necessarily … demonstrating better tactical capability. What we did see, however, was changes in the operational design … What they were going after changed.

So that really has been the bigger observation that I’ve personally had since 2013: This organization which I remember … being a disrupted terrorist network has operational art the way that I would expect an army to have. … Where does one get operational art? That doesn’t seem to come naturally; seems like it should come from being trained inside of a former military. … Does it have commanders who had been part of Iraq’s former army—who have operational art because they gained it inside of a former military institution? That is still my reigning hypothesis because I don’t think it spontaneously arrives. I think it’s a legacy of former training. But if that’s true … then AQI had it all along, but they just couldn’t use it.

This is the crucial point: IS’s leaders now were all early members of AQI, which was a small organization, led by Zarqawi, whose hatred for impious Ba’athists is well-known. Even in late 2006, when Zarqawi was dead and IS’s predecessor was struggling, it called on the FREs to join only “on condition that the applicant must know, at a minimum, three sections of the Holy Qur’an by rote and must pass an ideological examination.” There was no “Ba’athist” takeover of IS; the FREs rose because their military skills made them the last men standing as IS’s leadership was ground down under external pressure.

Case Studies

The classic case is Samir al-Khlifawi (Haji Bakr), an intelligence officer from an elite Saddam regime unit, who joined AQI in 2003, meeting personally with Zarqawi in Anbar. Imprisoned through some of IS’s worst times and competent enough to ride out the nadir in 2008-10, al-Khlifawi became the deputy to the “caliph,” Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, and was key in IS’s recovery and its expansion into Syria.

Reuters lists as examples of “Ba’athists” within IS: Ayman Sabawi al-Ibrahim, Saddam’s nephew (son of Sabawi Ibrahim Hasan al-Tikriti, a brother of Saddam’s and the above-mentioned Barzan); Raad Hassan, Saddam’s cousin; Ayad Hamid al-Jumaili; Fadel al-Hiyali; and Waleed Jassem al-Alwani (Abu Ahmad al-Alwani). Where the biographies of these figures are known it doesn’t demonstrate them having “became radicalised in the early years after Saddam’s ouster,” but rather men that had taken to Islamism before the end of the Saddam regime.

Ayman Sabawi was born in 1971, so was only twenty-two when the Faith Campaign began, which is certainly old enough to have been caught in the religious upwelling that was particularly effective over Iraqi youth. Interestingly, when Ayman Sabawi was sanctioned by the European Union in 2005, they also sanctioned his brother, Ibrahim Sabawi Ibrahim, one of whose addresses was Zabadani, the town west of Damascus where the Assad regime held meetings with elements of the fallen Saddam regime and IS to plan terrorism against the New Iraq. Arrested in 2005, Ayman Sabawi was broken free in 2006 and little has been heard of him since. Ibrahim Sabawi popped back up recently in a death notice.

Hassan was also a young man when the regime fell, and both he and Sabawi are more symbolic than influential in any case: IS makes a specific point of their repentance for their past beliefs, the message being that if even the sons of such senior Ba’athists have seen that IS is the way forward, everyone else should, too.

Other than being a former officer in Saddam’s army, very little is known about al-Alwani, including whether or not he is alive. Some reports at the time of the Iraq offensive said al-Alwani was head of the Military Council, IS’s most important institution, but this is untrue. Adnan Ismail Najem al-Bilawi (Abu Abdulrahman al-Bilawi) was the head of the Military Council until several days before Mosul fell, and captured documents show that al-Bilawi was replaced by Adnan as-Suwaydawi (Abu Muhannad as-Suwaydawi a.k.a. Haji Dawood). Reports from British tabloids in February 2015 said that al-Alwani had been killed in late 2014—probably in the November 7 airstrike that hit an IS gathering—but no confirmation has ever emerged, even from Baghdad which frequently and prematurely claims the demise of IS leaders.

When as-Suwaydawi was killed in May 2015, he was replaced by al-Hiyali (a.k.a. Abu Muslim al-Turkmani a.k.a. Haji Mutazz), the governor of IS-held territory in Iraq and the caliph’s overall deputy. Al-Hiyali is a perfect example of somebody who was Islamized during Saddam’s time and was primed to join the jihadi-Salafists before 2003. Personally close to Saddam and ad-Douri, al-Hiyali was imprisoned during the American regency in Iraq for conducting terrorism with IS’s predecessors and was among those who planned IS’s revival in Iraq and expansion into Syria.

Then there is al-Jumaili. Described as “the overall head of Amniya in Iraq and Syria,” al-Jumaili is “a former Saddam-era intelligence officer from Fallujah … who joined the Sunni insurgency after the U.S.-led invasion and now answers directly to Baghdadi”. The amniyat are the security units operated by the Security and Intelligence Council (SIC), a subset of the Military Council, which guard the caliph personally and are distributed through IS-held areas to ensure the loyalty of IS members, both in an ordinary security sense (preventing unsanctioned criminality) and in the counter-intelligence sense, as so well explained by Michael Weiss and Hassan Hassan in their book (p. 211) and by more recent revelations acquired by Weiss from an IS defector. In short, the amniyat are the squads that conduct the arrests and assassinations to guard the caliph and the caliphate against threats, internal and external. Al-Jumaili took over this job from Abu Ali al-Anbari, who had been the governor of Syria while al-Hiyali was the governor of Iraq. Al-Anbari replaced al-Hiyali at the head of the Military Council after al-Hiyali was killed in August, and passed the SIC/amniyat file to al-Jumaili. Al-Jumaili was also personally responsible for the qisas (retribution) videos showing the drowning of captives in a cage and the blowing up of men in a car with an RPG.

Also fitting the pattern of an FRE converted to Sunni militancy by the Saddam regime who went on to use his local and military knowledge to IS’s advantage is Muwafaq al-Kharmoush (Abu Saleh), IS’s “finance minister” in Iraq (whether his role has been expanded since Fathi at-Tunisi, a.k.a. Abu Sayyaf al-Iraqi, was killed in May is unclear). Overseeing the extortion networks and directly involved in IS’s oil trade with the Assad regime, al-Kharmoush was allegedly killed in an American airstrike last month. Al-Kharmoush was “a former mukhabarat (intelligence) officer during Saddam’s time … who turned to religion in the late 1990s”.

The intellectual property of the Saddam regime helps IS in its international operations as well. It was an FRE, Wissam az-Zubaydi (Abu Nabil al-Anbari a.k.a. Abu al-Mughirah al-Qahtani), whose current state of health is a matter of some controversy, who was dispatched by IS to Libya to oversee the construction of IS’s network in that country by peeling away al-Qaeda loyalists and annexing local profit-making criminal enterprises.

Conclusion

To date the migration of FREs into IS to the last few years misses the timeline of the evolution of JTJ/AQI, as does dating the phenomena of Iraqi military-intelligence officials adopting Islamism or collaborating with jihadi-Salafists to the post-2003 period. The networks by which foreign Sunni jihadists entered Iraq predate 2003, either being formed with regime complicity by Zarqawi in 2002, or directly formed by the regime much earlier as part of Saddam’s alliance with the Islamists in his foreign policy. Ad-Douri found it convenient to mobilize these foreign networks, and supply them with resources once they reached Iraq, to frustrate the attempt to build a democratic government in Iraq, while many individual FREs had become Islamists during Saddam’s time and joined IS’s predecessors in the first few years after Saddam’s fall when the group was small and entry was highly selective. The capabilities on display from IS were thus there all along but were held in check until 2011 by the Anglo-American military forces stationed in Iraq.

(IS, of course, has also benefited from the Syrian war and its old connections with the Assad regime, without which it could not have risen so quickly. IS moved in after the Syrian opposition had defeated the Assad regime to consolidate control in liberated areas. Because IS was focussed on pushing the rebels out of areas, not on Assad, and because IS’s cruelty made such good propaganda to discredit the whole opposition, Assad allowed IS to grow. IS would eventually use Syria as a launchpad for the lightning strike into Iraq, where IS had been busily shaping the social and security environment since before the U.S. had even left so it had de facto control in large areas before it openly took over.)

The Saddam regime’s turn to Islamization was in all probability cynical in origin, an effort to secure legitimacy as Saddam’s regime fought for its life in the war it started with the theocratic regime in Iran. Tehran constantly accused Saddam’s regime of being irreligious and internal documents show the Saddam regime knew this propaganda was damaging its standing with the Iraqi population. The Faith Campaign directly produced a religious movement and operated in alliance with the “pure” Salafi Trend, which the regime both consciously ceased repressing and lost the capacity to restrain. Many “pure” Salafists found that their differences with the regime were now minimal enough that they could serve in its administration, though those at the more takfir-inclined end of the spectrum had begun a low-level insurgency, with bombing attacks in Baghdad and elsewhere, by 2000. The Faith Campaign’s trapdoor—people finding they could take Salafism without Saddamism—was especially acute in the security services that were sent to infiltrate and guide the mosques and religious brotherhoods that the Saddam regime now so publicly supported.

The Faith Campaign’s ecumenical intent also wholly backfired, causing a final breakdown of State-Shi’i relations and heightening sectarianism to levels previously unrecorded. The Campaign’s empowerment of mid-level clerics fundamentally transformed Iraqi society, notably in the Sunni areas, which were also altered by the tribes being tasked with manning the ad-Douri-directed cross-border networks that were set up to evade the sanctions. The turn to religion for solace during the devastating sanctions-plus-Saddam period reinforced many of these trends.

To put it simply, the Saddam regime’s reputation for keeping a lid on religious militancy and sectarianism is exactly wrong; by commission and omission it brought both things to levels Iraq has scarcely ever known in its history. The U.S. prisons in Iraq turned into little more than factories for IS’s predecessor to recruit and the catch-and-release policy was a dismal failure. Disbanding the army should also have been done differently. These are not on the same scale for influence as the wholesale transformation of Iraqi society by Saddam’s last fifteen years, however. The Faith Campaign and the accompanying patronage networks laid the foundations for something like IS, ideologically and materially, long before the Coalition invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Post has been corrected regarding the role of Iyad al-Jumaili and the profile of Ayman Sabawi, and updated regarding Zarqawi’s movements in and around Iraq in 2002

Pingback: ISIS was coming even without the invasion of Iraq

Reblogged this on Nervana and commented:

This post is a must read for those among the progressive liberals and leftists in the US and UK who assert that the Islamic State is the result of the Iraq war.

The invasion of Iraq was wrong for many reasons, but the the rise of the Islamic State is not one of them.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Ned Hamson's Second Line View of the News.

LikeLike

While I think this article makes some interesting and important points, I think the conclusions are too broad. The notion that ISIS would have arisen without some ungoverned space in which to grow is I think suspect.

On a more substantive point, I would question the characterization of Abu Sayyaf Group as ‘al-Qaeda’s’. There was certainly material co-operation in the 90’s. However as far as I am aware material links died with ASG founder Abdurajak Abubakar Janjalani in December ’98. By ’02 ASG was significantly fragmented and had little central direction. Furthermore it is unclear whether Sgt Jackson was the primary target of the bomb attack in Zamboanga in October ’02.

LikeLike

Pingback: ISIS, brought to you by…Saddam Hussein? | and that's the way it was

Reblogged this on A Riverside View and commented:

Interesting article

LikeLike

Pingback: On the Effort to Exonerate Team USA for the Rise of ISIS: Guest Analysis by David Mizner – Levant Report

Pingback: The Effort To Exonerate Team USA for the Rise of ISIS – Antiwar.com | Sport Goods Mart

Pingback: Donald Trump is Wrong (Again): Saddam Hussein Supported Terrorism | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Islamic State’s Official Biography of the Caliph’s Deputy | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: How the Islamic State’s Caliph Responded to Defeat Last Time | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: A Myth Revisited: “Saddam Hussein Had No Connection To Al-Qaeda” | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Official Declaration that Made Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi Leader of the Islamic State | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: How Powerful is the Islamic State in Saudi Arabia? | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Islamic State’s Media Apparatus and its New Spokesman | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Mosul Operation and Saddam’s Long Shadow | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The End of the Beginning for the Islamic State in Libya | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Raqqa Doesn’t Want to Be Liberated By the West’s Partners | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Al-Qaeda Leader Profiles the Founder of the Islamic State | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Failure of the United Nations in Syria | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: One More Time on Saddam and the Islamic State | Kyle Orton's Blog

Pingback: Reviewing the Iraqi Surge and Awakening | Kyle Orton's Blog

Pingback: The Islamic State's Official Biography of the Caliph's Deputy | Kyle Orton's Blog

Pingback: Islamic State Profiles the Godfather of its Media Department | Kyle Orton's Blog

Pingback: Donald Trump is Wrong (Again): Saddam Hussein Supported Terrorism - Kyle Orton's Blog