By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 2 September 2017

The most recent issue of Perspectives on Terrorism had a paper by Ronen Zeidel entitled, ‘The Dawa’ish: A Collective Profile of IS Commanders’, which was “the first attempt to provide a comprehensive collective profile of commanders and leaders of the Islamic State (IS)”. Based on “an inventory of over 600 names”, the paper assessed the nationality, ethnicity, and tribal origins not just of the very senior IS commanders, but those lower down, a novel and much-needed line of investigation. Zeidel found that these commanders of the IS movement are or were overwhelmingly Iraqi and Sunni Arab, with an important Turkoman contingent.

Zeidel’s findings are important for drawing attention again to the local-revolutionary character of an organisation that gets a great deal of attention for its foreign fighters and external attacks, especially in the West, but which only a recently acquired global reach—and, indeed, only recently needed to: until 2011, the West was easily reachable since it had troops on the ground in Iraq, so the incentive to invest resources in creating a foreign terrorist apparatus was minimal.

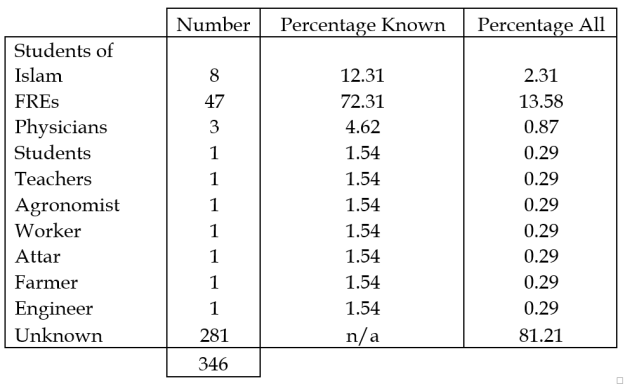

One small part of Zeidel’s work has created something of a storm, however. Zeidel gives the occupation held by these commanders and, for those where this was known, 72% of them were former regime elements (FREs) from the dictatorship of Saddam Husayn. This reignited the argument over how important the FREs have been to IS.

STATISTICS AND NARRATIVES

The striking statistic becomes less definitive when it is factored in that the occupations for 81% of the sample were unknown:

There are also good reasons to suspect that this trend would not extend to the “unknowns” because there is a bias in favour of discovering the FREs. The state documents and databases listing the employees of the fallen Saddam regime, whether in its security apparatus or the Ba’th Party, are now in the hands of the American and Iraqi governments. There is also an open source selection bias in favour of reporting an FRE background, as opposed to, say, a farmer or labourer.

After the role of the FREs was initially under-reported, an overcorrection occurred—led by Christoph Reuter’s April 2015 profile of Samir al-Khlifawi (Haji Bakr) in Der Spiegel—that suggested, if not outright stated, that IS was merely the Ba’th Party wrapped in a black flag. This narrative, casting IS as crypto-Ba’thists, was pushed with particular vigour because it served a large number of political agendas, in the region and in the West.

In Iraq, both Shi’a and Kurdish political factions believed or presented this picture as it mobilized the appropriate degree of revulsion among their communities. Islamist insurgent groups in Syria that wished to discredit IS while avoiding ideological contamination also advanced this idea. For the states around Iraq, as well as for Western commentators favourably disposed to one or other dictatorship, notably those supportive of Bashar al-Asad, this narrative allowed an indictment of “regime change” adventurism. Among Westerners, there were those who sought to blame the region’s ills on George W. Bush and those who wished to divorce IS in every way from Islam, and both found the Ba’th-reborn explanation for IS convenient.

In a recent paper, Craig Whiteside dispensed with these myths—and several others, including those surrounding Izzat al-Duri, Saddam’s deputy when the regime came down and the nominal leader of Jaysh al-Naqshbandi, an Islamist-Ba’thist insurgent group, afterwards. IS is a religious movement and recruited only those who were religiously acceptable; where that has included FREs, they were not ideological “Ba’thists” and usually had not been for some time. There is no imprint of Ba’thist ideology on IS’s jihadi-salafism. Even in terms of IS’s structure, the departmental layout is practically identical to that which al-Qaeda developed many years before in Taliban Afghanistan.

THERE FROM THE BEGINNING

One of Whiteside’s more contested conclusions is that the FREs are inconsequential to IS’s operational security and counter-intelligence capabilities. “[C]landestine organizations that survive the punishment that the Islamic State has endured for over a decade, by the very best counter-terrorism forces in the world, eventually develop excellent operational security measures”, says Whiteside.

There is little contest about the core of Whiteside’s conclusion, though:

The Islamic State, like its rival al-Qaeda, deliberately recruited former regime members for their military experience early in their existence. Once in the organization, they almost exclusively served in military and command roles—a key function in an insurgency to be sure—but not the most important. In revolutionary war, it is the political and social aspects of the conflict that dominate the action and will determine the outcome. The technical requirements of modern warfare and weaponry absolutely demand an expertise in military operations. But outside of war-fighting functions and internal security, the former regime members in the Islamic State were simply not to be found. … Certainly the FRE contributed in a significant manner to the hybrid military campaign that consolidated extensive terrain in Syria and Iraq between 2012 and 2014, and this recognition certainly deserves the attention it has received. The problem with this attention is the need for balance; in looking at it from the Islamic State perspective, their legends are presented as a broad mix of people: homegrown Salafis, FRE, and immigrants.

It is a key point that in revolutionary warfare, ideological-political considerations are more important than military developments, which come and go. And while FREs might have been conspicuously absent in the media and religious departments that IS values so much, it is equally important to note the FREs’ contribution to IS’s military success—a key part of building the brand that has enabled the propaganda-recruitment work. This has been true from the beginning.

As Hassan Hassan, who co-wrote a book with Michael Weiss, ISIS: Inside the Army of Terror, which goes into great detail about the FRE involvement in IS, pointed out after the release of Zeidel’s paper: IS itself attests to the role played by “repentant officers” from the first days in both the group’s operations and in training the organization’s younger cadres, a legacy that has and will long outlast the FREs.

This pattern can be seen in the first IS camp in Iraq at Rawa, set up while Saddam was still in office. It is true that the camp was nominally run by Abu Raghd, a Saudi veteran of the jihad against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, and a key instructor at the camp was Mustafa Ramadan Darwish (Abu Muhammad al-Lubnani), a Lebanese-Danish Kurd. It is also true that an absolutely key individual for the recruitment and training at this camp was Ghassan al-Rawi (Abu Ubayda), a former officer in Saddam’s security services. Similarly, while, Nidal Arabiyat, a Jordanian jihadist, put together most of the bombs for IS’s early military-terrorist campaign, he was assisted in getting the devices into place by tapping into the logistical knowhow and personal connections of Thamir Mubarak al-Rishawi, an ex-Saddamist.

Part of the shift back against the view of the FREs as important has involved a tendency to point to examples where IS leaders were originally misidentified as FREs, like Abu Ayman al-Iraqi and Abu Ali al-Anbari. Abu Ayman was originally thought to be Adnan al-Suwaydawi, who was also known as Abu Muhannad al-Suwaydawi, a former intelligence officer in al-Khlifawi’s unit. As Romain Caillet has shown, the notoriously savage Abu Ayman was a different, younger man to al-Suwaydawi, and had no connection to Saddam’s regime. [UPDATE: IS published a biography of Abu Ayman, giving his real name as Ali Aswad al-Jiburi.]

The case of Abu Ali is not quite so clear cut. Yes, Abu Ali, the caliph’s deputy until he was killed in March 2016, transpired to be Abdurrahman al-Qaduli, a jihadi cleric who had worked to form an underground organization to challenge Saddam’s regime in the 1990s. But al-Qaduli had carried this out by recruiting Fadel al-Hiyali, whose kunyas include Haji Mutaz, Abu Mutaz al-Qurayshi, and Abu Muslim al-Turkmani. Al-Hiyali was a member of Saddam’s special forces and had previously been in istikhbarat (military intelligence), and al-Hiyali trained this cell. Al-Hiyali and al-Qaduli later advanced through IS together, al-Hiyali having been overall number-two when he was killed in August 2015.

One can take it back further, to al-Qaeda’s camps in Afghanistan, where there was an imprint of the Saddam regime’s military doctrine to its tactical training. Nashwan Abdulbaqi (Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi), an Iraqi Kurd and major in Saddam’s army, had gone to Afghanistan in 1992, joined al-Qaeda soon after Usama bin Ladin arrived in 1996, and was using his Iraqi Army manual to train jihadists by the end of the 1990s. Abdulbaqi was among the most senior members of al-Qaeda’s military effort, and pushed for al-Qaeda and the Arab jihadists to get more involved in the Taliban’s fight against the Northern Alliance. After the Taliban regime collapsed, Abdulbaqi was key to al-Qaeda’s dealings with IS, until he was arrested in Turkey in 2006 and transferred to Guantanamo Bay detention facility.

But, to return to Iraq in the immediate aftermath of Saddam. As Whiteside notes, IS “deliberately recruited former regime members for their military experience early in their existence” and, elsewhere in the paper, Whiteside adds that the IS movement had “deliberately recruited capable (and religiously acceptable) individuals with military experience from 2003-2006 when they had a shortfall in this particular skill”. The FREs that have risen to prominence—the chief of staff, Muhammad al-Nada al-Jiburi (Abu al-Bashair), and the subsequent heads of IS’s Military Council between 2011 and 2015, Samir al-Khlifawi, Adnan al-Bilawi (Abu Abdurrahman al-Bilawi), Adnan al-Suwaydawi, and Fadel al-Hiyali; the provincial governor who laid down the basis for a statelet in Libya, Wissam al-Zubaydi (Abu Nabil al-Anbari); the current deputy, Iyad al-Ubaydi (Abu Saleh al-Hayfa), and the current head of the amniyat (internal security agency), Iyad al-Jumayli (Abu Yahya al-Iraqi)—all joined IS in the early post-Saddam period.[1]

Thus, the extent of the FREs involvement can be seen, and even if the most extreme (and almost certainly false) assumption about this data set—that the identified FREs are the only ones—it would still mean they were 15%. It is not quite comparing like with like to treat the FREs’ influence as just one more category. This is a societal sector that is cohesive within itself, has disproportionate wealth, military and administrative training and experience, and access to the patronage and tribal networks that acted as pillars of the old regime.

INTERNAL OR IMPOSED?

A supplementary question is why this happened. Zeidel says that the FREs “joined the IS on [Abu Bakr] al-Baghdadi’s invitation and initiative, as late as 2010. They are not particularly religious”. This is categorically mistaken. As demonstrated above, these men all joined earlier. Moreover, until 2005, the IS movement was a small, foreign-led jihadi outfit amid an insurgency dominated by Ba’thi-Islamists and Saddam’s tribal clientele who were supported with the looted treasury of the fallen regime. There was no incentive on either side for impious, power-hungry Ba’thists to join IS. Those who joined made an ideological choice.

To put it a different way: Why were so many members of Saddam’s security forces religiously acceptable to IS? And why, as Whiteside notes, was there “such a robust underground [salafi] community” in Iraq for IS’s founder, Ahmad al-Khalayleh (Abu Musab al-Zarqawi), to exploit when he arrived in 2002. One answer is that the destruction of the Iraqi state in 2003, the sectarian mayhem of 2004-07, and the autocratic nature of Nuri al-Maliki’s regime until 2014 opened the way to IS. But, if one simply refers to the timeline, that doesn’t get us very far. The same with other explanations that look to other outsiders like Saudi Arabia and “Wahhabism”. These men were primed for jihadism by 2003, which is to say their transition to Islamist extremism happened under Saddam. An alternative explanation would look to the religious, political, and sociological changes engineered by the Saddam regime in its final decade or so in office.

* * *

Notes

[1] According to his official biography, Samir al-Khlifawi (Haji Bakr) gave his bay’a (oath of allegiance) to the IS movement in 2004. But Adnan al-Asadi, an MP for al-Maliki’s State of Law Coalition and acting head of the Interior Ministry, claimed that this was mistaken when he ostensibly read from al-Khlifawi’s prison files during an interview on an Al-Arabiya television program, “Death Industry,” on 14 February 2014, about a month after al-Khlifawi was killed in Aleppo by the Syrian opposition. Al-Asadi said that Ziyad Al-Hadithi (Abu Zinah), an Iraqi protégé of Mustafa Darwish (Abu Muhammad al-Lubnani), the first IS military emir and Zarqawi’s second overall deputy (2004-05), recruited al-Khlifawi in Camp Bucca. Al-Khlifawi was imprisoned between 2006 and 2008. Allegedly, al-Khlifawi had been a member of Jaysh al-Islami fi’l-Iraq (The Islamic Army of Iraq), an insurgent group stocked with FREs that operated with an Islamist veneer and very little actual religious motivation. When the Sunni community split in 2007, most of JAI joined the Sahwa (Awakening) against IS.

Originally published at The Henry Jackson Society. Post has been updated

Pingback: America Sanctions the Islamic State’s Intelligence Chief | Kyle Orton's Blog

Pingback: Islamic State Profiles the Godfather of its Media Department | Kyle Orton's Blog