By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on August 13, 2016

PYD/YPG fighters

The Islamic State (IS) was driven from the city of Manbij yesterday, a key supply route to the Turkish border in northern Syria, the conclusion of an operation launched on 31 May by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a front-group for the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), represented in Syria by the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and its armed wing, the People’s Protection Units (YPG). The SDF was backed by U.S. airstrikes. It is difficult not to see the defeat of IS as a positive development. It is, however, worth more closely examining the forces that are being enabled by Western power to fasten their rule across northern Syria, whose vision is deeply problematic—even in narrow terms of the fight against IS.

The PKK in Syria

The constitution for the Rojava-Northern Syria Democratic Federal System—to which we can be sure Manbij will be added—passed on 1 July 2016 and declares Qamishli its capital. The Federal System is controlled by Democratic Society Movement (TEV-DEM), which is a political coalition dominated by the PYD.

When the U.S. began overt weapons supplies, it claimed to be supporting the “Syrian Arab Coalition” (SAC) within the SDF, but this is a fiction. The YPG/PYD remains in complete control of the SDF. People on the ground had never heard of the SAC, which was bluntly described as a “ploy” by one U.S. official to allow the U.S. to arm the YPG. The Arab detachments are clearly dependent on the YPG. The Arab SDF did not even have the logistical capacity to receive weapons airdropped to them. YPG General Commander Sipan Hemo acknowledged that the “weapons airdropped to SDF … is important to us as YPG” because it was a mark of increased coordination with the Americans. The Arab SDF was designed as a political cover for this cooperation, and the YPG clearly intends to keep them as a means of facilitating this coordination without allowing them to assert an independent course.

Fehman Husayn (Bahoz Erdal)

The PYD was founded in 2003 as the “Syrian branch of the PKK,” and indeed “almost all YPG fighters have a PKK background.” There remain those who deny that this is what the PYD is, the State Department among them, no doubt for reasons to do with the PKK’s presence on the list of foreign terrorist organizations. There has been a public admission by the U.S. Defence Secretary of “substantial ties” between the PYD and the PKK, and the reality is that the PYD/YPG is a wholly integrated component of the PKK, subordinate to its leadership in the Qandil Mountains and run by PKK-trained operatives who moved into Syria in large numbers in 2011 and 2012. The YPG’s own casualty figures attest to the substantial number of PKK troops from Turkey and elsewhere in the YPG’s ranks, and the group’s own fighters have been candid about the YPG’s nature. “It’s all PKK but different branches,” an Iranian Kurdish fighter, Zind Ruken, told The Wall Street Journal. “Sometimes I’m a PKK, sometimes I’m a PJAK, sometimes I’m a YPG. It doesn’t really matter. They are all members of the PKK.” An additional piece of evidence in this regard was supplied by the reported death of Fehman Husayn (Bahoz Erdal) inside Syria on 9 July.

Husayn is reported dead semi-regularly, and supposedly denied his demise this time to Al-Jazeera. What is important here is that while Abdullah Ocalan remains the formal head of the PKK from his Turkish prison cell on Imrali Island, the day-to-day control of the organization has passed to a cadre of people that includes Husayn.

Cemil Bayik, Murat Karayilan

Husayn, a Syrian Kurd from Kobani, was reported to be inside Syria as early as the summer of 2012 and to be leading the military side of the PYD/YPG, while the more political aspects were left in the hands of Saleh Muslim Muhammad, who is himself close to Murat Karayilan (Cemal), the leader of the PKK after Ocalan was imprisoned.

Even if the YPG was primarily locally-focused, it would not invalidate the fact that it was the PKK. Just as Jabhat al-Nusra—or Jabhat Fatah al-Sham (JFS)—is no less al-Qaeda for having a local focus, so it is with the PYD/YPG as a totally integrated part of the PKK’s transnational political structure, the Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK). But the YPG—already far more directly subordinate to the PKK than JFS is to al-Qaeda—has not been allowed to “go local”.

At the PKK’s Ninth Congress in July 2013, Karayilan, a renowned military leader who was known to be more compromise-minded and to favour more decentralization for the PKK’s branches, was replaced by Turkey-centric radicals Cemil Bayik (Cuma) and Bese Hozat (Hulya Oran), who now jointly chair the KCK. Karayilan became the commander-in-chief, heading the PKK’s military units, the People’s Defence Forces (HPG), and his deputy was Husayn, like Bayik, a known hardliner. Husayn is also believed to be the commander of the Kurdistan Freedom Falcons (TAK), a special forces-style outfit and a cut-out for the PKK that has claimed some of the more atrocious, civilian-focused terrorist attacks of late. Also working under Karayilan as a de facto second deputy was Nurettin Halef al-Muhammed (Nurettin Sofi), commanding the Amed and Botan regions. By some accounts, al-Muhammed has led the YPG since 2013 and his deputy is Ferhat Abdi Sahin (Sahin Cilo), a Syrian PKK commander who previously ran the HPG.

The remaining spots on the six-person KCK executive committee with Karayilan, Bayik, and Hozat were occupied by: Nuriye Kesbir (Sozdar Avesta), Mustafa Karasu (Huseyin Ali or Avaresh), and “Elif Pazarcik” or “Ronahi”. Some accounts include Duran Kalkan (Selahattin Abbas) as among the top tier of the PKK. [UPDATE: In late August 2016, after the Turkish intervention in Syria, Kalkan publicly threatened to send more PKK troops to Syria to bolster the YPG.]

Democratic Confederalism

Abdullah Ocalan (source)

Even when it is conceded that the U.S.-led Coalition is supporting the PKK in Syria, an argument has been made that the organization has undergone a transformation away from the Stalinist-chauvinist cocktail of its founding. At the time of the March declaration of the Federal System, a spokesman for the TEV-DEM said it would be based on “Democratic Confederalism“. This ideology is the brainchild of Abdullah Ocalan, who is also known as “Apo” (hence the PKK’s ideology has been called “Apoism”).

The PKK at its founding in November 1978 was a Marxist-Leninist organization, even if this ideology was “secondary to the PKK’s nationalist drive” (p. 244) and the cult of its leader. By the 1990s Ocalan was said to have already showing signs of looking beyond Bolshevism and nationalism after the collapse of the Soviet Union. In prison, Ocalan’s evolution accelerated and Apoism formally abandoned outright separatism—indeed abandons the demand for a state at all—and adopts a hodgepodge vision of environmentalism, anarchism, and radical democracy.

Ocalan was arrested in Kenya on 15 February 1999, soon after being kicked out of Syria, and quickly demonstrated (p. 286-88) how firmly in control he remained on the ground. At the Seventh Conference in January 2000, the PKK formally renounced separatism, a bitter blow for many of the PKK old guard, and a number quit altogether and sought asylum in Europe.

In a book written in prison and published in 2011—originally submitted as part of an appeal to the European Court of Human Rights and then adopted as a manifesto at the 2002 Congress—Ocalan distanced himself from communism and offered ideological self-criticisms (“The PKK’s founding manifesto reflected the Zeitgeist of the time … [but] did not … allow for a realistic approach … Real socialism has collapsed and the democratic civilization has proved its advantages”) and even some practical ones, conceding that the PKK ignored “signs coming from the Turkish authorities that a solution could be reached,” and fought on believing it was a “virtue to resist … compromise”. What began as self-defence ended as an “offensive” by the PKK, says Ocalan, “where we killed the best of our own comrades” and plunged into a “dirty, brutal war”. And for all that the status quo still held.

The final theoretical break of Apoism from the tyrannical Stalinism of its inception came in 2005, when Ocalan announced his conversion to an eco-anarchist form of direct democracy, inspired by Murray Bookchin (1921-2006), an American author whose youthful communism had given way to “libertarian socialism”—a version of communitarian anarchism.

After reading a number of Bookchin’s books, Ocalan and Bookchin began corresponding in 2004 and in March 2005 Ocalan issued his formal declaration abandoning Marxism-Leninism in favour of Democratic Confederalism and renouncing the idea of creating a Kurdish state:

The only way out of this situation is to establish a democratic confederal system … Democratic confederalism of Kurdistan is not a state system, but a democratic system of the people without a state. … It is based on the freedoms of political, social, economic, cultural, sexual and ethnic rights.

Ocalan called for the establishment of a Koma Komalên Kurdistan (KKK), a prototype for the KCK that would be formed in 2007. It should be noted that this move toward forming national branches outside Turkey in the Kurdish-majority zones of Iraq, Syria, and Iran was driven, at least in part, by the post-2001 environment that made the terrorism designation of the PKK even more of a liability. Having different names in different countries helped evade this legal difficulty.

Ocalan expanded on his ideology by publishing a short book simply called Democratic Confederalism (2011). Ocalan rejects the nation-state entirely as an instrument representing the “national governor of the worldwide capitalist system,” rather than the common people, and which provides pressure toward homogenization that “leads into assimilation and genocide.”

It is rather notable that Ocalan situates himself away from rationalism, and instead takes up a position at the point where religion and New Age dogma intersect, rejecting “positivist science” and secularism as forms of superstition divorced from the spiritual needs of the people.

Ocalan situates his struggle within anti-capitalism rather than nationalism. “Without opposition against the capitalist modernity there will be no place for the liberation of the peoples. This is why the founding of a Kurdish nation-state is not an option for me,” Ocalan writes. Democratic Confederalism is an “anti-nationalist” concept that aims to proceed “without questioning the existing political borders,” since only “the ruling class or the interests of the bourgeoisie” desire a Kurdish nation-state.

In defining Democratic Confederalism, Ocalan says it is a “non-state social paradigm” that is in practice “a democracy without a state,” which is “multi-cultural, anti-monopolistic and consensus-oriented,” is opposed to centralization and hierarchy, based on community and grassroots democracy, and has “ecology and feminism [as] central pillars.” Still, Ocalan does conclude that “overcoming the … nation-state, is a long process,” and a “total rejection” of the state in the short-term is unwise.

This structure, according to Ocalan, could begin with a federation of the four Kurdish-majority zones—in Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran—and then democratize the entire Middle East. Indeed, “global confederalism is not excluded”.

The PYD has used exactly this argument to contend that its Federal System can be expanded to allow local, democratic rule across all of Syria. This has naturally met with some scepticism given how the PYD has actually behaved.

The PKK in Practice

While Ocalan gives every indication of having undergone a genuine intellectual evolution and having formally imposed this on the PKK, the PKK in practice has shown itself bound by its founding. “Nothing much changed when the [Bashar al-Assad] regime withdrew … and the PYD took over,” a local resident of Efrin told Robin Yassin-Kassab and Leila al-Shami in their book Burning Country. Kurdish journalist Hussein Omer compared the PYD’s rule, in its seizure of the various branches of society, to the Ba’ath Party’s. The much-persecuted Kurdish opposition to the PYD has made the same comparison between the PYD and the Ba’athist system.

A notable example is the schools. There have been contests in rebel-held areas between the nationalist opposition and the Islamists who try to impose ideological control children’s education; this has occurred in Kurdish areas as well. In September 2015, the PYD introduced a new curriculum in the areas it controls and began filling the schools with a cadre of its own teachers. This was denounced by teachers and others as spreading a “totalitarian ideology”. Demonstrations broke out from parents who wanted their children taught Arabic and English alongside Kurdish, and a number of Kurdish parents sent their children to private schools where they could get an education without the political indoctrination.

The fleeing of civilians from combat zones is inevitable, but the PYD has taken steps toward preventing the return of Arab inhabitants, sometimes by threats of live fire, more often by demolishing homes. Amnesty International has also reported incidents of direct ethnic cleansing of Arabs, which have also been alleged elsewhere. The chauvinistic tendencies of the PYD have been seen not only against Sunni Arabs, but Turkomen.

The PYD was accused, on 23 February 2014, of massacring Arab civilians after the takeover of Tal Barak in the Hasaka Province. The PYD denied this, claiming it was IS “propaganda” aimed to “upset the Kurdish-Arab brotherhood”. But the PYD spokesman did concede that the PYD had “targeted the mercenaries” and appealed to “the authentic people” in the area to resist these groups. Given that PYD messaging frequently refers to all forms of opposition to its rule—whether armed Arab rebels or Kurdish political opposition—as hirelings of Turkey, this cryptic statement is not wholly encouraging. Tal Barak was not the first accusation of massacre against the PYD, nor would it be the last.

PYD militiamen fired on demonstrators in Amuda, who were demanding the release of political prisoners held by the PYD, on 27 June 2013, killing six people. The PYD were said (p. 46) to have killed seven Arabs with random machine-gun fire in al-Aghabish, a village near Tal Tamr, on 19 November 2013, and to have thereafter demolished twenty-seven homes. On 13 September 2014, PYD police forces are alleged (p. 5) to have killed forty-two people in al-Hajiya and Tal Khalil, and to have abducted twelve people from Marmeen, Aleppo, accusing them of being connected to al-Qaeda, before summarily executing them near Efrin on 29 November 2015.

Anti-PKK Kurdish demonstrations have been violently quelled by the PYD. Journalists face stern restrictions in PYD-held areas. Political opponents are arrested and there is torture in the prisons to extract confessions. Aid is exploited as a means of social control. Conscription is enforced, including for child soldiers. Artefacts are looted.

Ilham Ahmed

Ilham Ahmed, a long-term PKK member who now serves as a senior PYD official and a member of the executive of the TEV-DEM, contends that the PYD wants “self-administration, not autonomy”. In this sense, at least, the PYD wishes to remain part of Syria. The PYD ostensibly rejects the idea of a Kurdish administrative area, contending that this is too restrictive a basis for Rojava’s diverse population.

The main rival of the PYD is the Kurdish National Council (KNC or ENKS), the non-PKK coalition that was forced to move its operations outside Rojava in 2012 as the PYD consolidated control. The KNC has worked with the Syrian opposition and has close links with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). The KNC does want an explicitly Kurdish system, and for that reason opposes the Federal System constitution, proposing its own alternative that would be implemented in consultation with the Arab rebellion and the population living under PYD rule.

[Update] The PYD/PKK has engaged not only in the indiscriminate killings mentioned above, but in targeted assassinations against Kurdish oppositionists. This accusation is probably wrong when made of the late 2011 murder of Mishal Tammo, a central figure in the early protest movement among the Kurds. It is almost certainly true of the 2012 killings of Bahzed Dorsen and Nasreddin Birhek, senior officials in the KNC member party, the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Syria (PDK-S), the sister party of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), the premier governing party in Iraqi Kurdistan. Other KNC officials like Mahmud Wali (Abu Jandi) fell to assassins around the same time. In 2013, Kawa Khaled Hussein, a member of another KNC-aligned Kurdish party, the Azadi Party, was tortured to death in PYD custody.

The KNC has been allowed back into Rojava in a limited way, but it operates under systematic restrictions and 5,000 KNC-aligned troops (the “Rojava Peshmerga” or “Roj Pesh”) have been prevented from entering Rojava by the PYD with the help of Iran. Some Syrian Kurds, such as Ahmed Bonchaq, who have gone to train with the Roj Pesh have been assassinated, likely by PYD security forces. The KNC has thus been allowed a minimal presence in Rojava provided it does not alter the balance of power against the PYD—and even that might now be over.

On 13 August, the head of the Yekiti Party and overall head of the KNC, Ibrahim Biro, was arrested in Qamishli by the PYD, and expelled to Iraq, told by the PYD he would be murdered if he tried to return to Syria. Thirteen more Kurdish oppositionists, nine of them Yekiti members, including Hassan Saleh, who has been imprisoned multiple times for anti-Assad dissidence, and the rest from PDK-S, were kidnapped on 15 August. People who demonstrated against this repression were attacked on 16 August, and further abductions of KNC members took place the next day. [Update ends]

Despite stated ideological shifts and some autonomy by necessity—the three cantons in northern Syria are geographically dispersed—the old tendencies of exclusivism, centralization (especially in the social sphere, notably in education), and a deep authoritarianism remain the order of the day with the PKK.

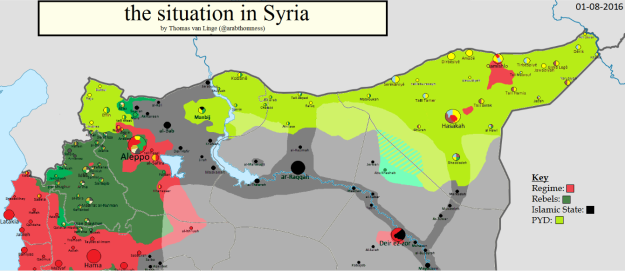

Situation map of northern Syria, 1 August 2016, by Thomas van Linge

In basic terms, the PYD has decided to lay stress on its ethno-linguistic pluralism in exchange for political monopoly, and the KNC has taken roughly the opposite track of an explicitly nationalist project but with political pluralism.

Despite all of these problems, the PYD has been accepted as the West’s primary proxy against IS.

The West and the PYD

Even as the U.S.’s train-and-equip program was collapsing in the summer of 2015, there was little concern in Washington because “in the eyes of the [Obama] administration, a better force had emerged—already trained, competent, organized—that posed little risk of abandoning the fight or worse yet, switching sides.” This was the PYD.

The PYD prevented an IS takeover of Kobani via massive U.S. airpower, and have been assisted with airstrikes since then in driving IS from Tel Abyad, Hasaka City, al-Hawl, Shadadi, and now Manbij. The PYD are not regarded as legitimate by the populations now under their rule in these places, giving IS political material towards its revival, and that is before the criminal behaviour is factored in.

The PYD’s sectarian crimes against Arab residents were documented after the very first operation that gave them control of Arab-dominated territory in Tel Abyad, poisoning the atmosphere ever-afterwards. Local residents reported to Amnesty that the PYD “threatened us with U.S. coalition strikes, saying that if we did not leave they would tell the U.S. we were IS.” The PYD received no sanction from its American backers for doing this—nor was it even challenged to deny that it had (at least in public). Tel Abyad convinced “many Arabs that living under the control of Kurdish forces was a worse fate than supporting ISIS.” A practical example came in February, when 30,000 Arab residents of Shadadi fled into IS-held areas after the PYD took the town.

There was no American reaction when the PYD—with Russian support—violated the three-way deal brokered with Turkey that had been intended to keep the PYD east of the Euphrates in exchange for Ankara not imposing a “safe zone” along the border that was both al-Qaeda- and PYD-free. And the U.S. did not react when the PYD coordinated the assault on American assets in Azaz with Russia in February, sparking outright rebel-PYD warfare, nor when the PYD closed the pro-regime coalition’s siege around rebel-held eastern Aleppo City on 27 July.

If the PYD was the only way to defeat IS, the lack of Western resistance to its maximalism would make more sense. But the PYD cannot—even if it wanted to—liberate the whole country. The Western posture seems to be a facet of the monomaniacally IS-focused policy, also seen in Iraq with the Iranian-controlled Shi’a militias, that allows any force labelled “anti-IS” at least a hearing.

This notion of the PYD as the most effective anti-IS force in Syria is based on several fallacies, primary among them not factoring in the effect of U.S. airstrikes in aiding the PYD and ignoring the rebellion’s considerable—and lasting—success against IS without such support. There are stringent restrictions on the will, capacity, and political legitimacy that the PYD operates under.

The PYD has no interest in shedding its blood to rule over hostile Arab populations beyond those necessary to link up Jazeera and Kobani with Efrin. And pushing the PYD to try—as a quid pro quo for accepting de facto PYD autonomy—not only allows IS a political situation it can exploit but overstretches the PYD and gives IS military opportunities. The PYD probably has 10,000 to 15,000 standing troops, with another 20,000 to 30,000 reservists. Well-trained as they are, they have limits.

There will therefore have to be a rebel component to the anti-IS effort, but the uncritical Western embrace of the PYD, even when it attacks Western-supported nationalist rebels, is setting up a power imbalance between the rebellion and the PYD that is damaging the anti-IS cause in the present, strengthening al-Qaeda, which is able to offer itself to the opposition as a protector, and over the long-term creating dynamics that could easily lead to another conflict.

The PYD and the Media

Grant it to the PYD: their use of media to enhance their support, especially when aimed at Western audiences, has been nothing short of brilliant. Understanding Western sentiment, the PYD has built its appeal on three pillars: a common cause against the jihadists, the Kurds’ long history of dispossession and persecution, and secularism.

An example of the complexity of the common cause argument—which ignores the PYD’s own agenda, namely state-building—is that while the PYD/PKK takes—deserved—credit for helping break the IS siege of Sinjar, the group obscures its role in using the Yazidi cause to increase its influence in local politics against another U.S. ally, the KRG.

The PYD might only be one faction of Kurdish opinion, but to much of the international media they have become “the Syrian Kurds,” an advantageous position that is among the things that has made criticism so marginal—nobody wants to an attack an entire people, especially when they are so embattled and apparently share our values.

The secular point is the most disseminated by the PYD. In Manbij yesterday, the pictures after IS fell showed women burning burkas and smoking, and men shaving their beards. The PYD’s female fighters have even convinced otherwise-pacifist commentators that the West should be engaged in Syria’s fight on the PYD’s side.

The idea of the PYD as the most, if not the sole, useful anti-IS force now has wide currency in policy circles and the popular media.

In rebel-held areas, the Assad regime and IS made it too dangerous for foreign journalists and then filled the vacuum with their own propaganda—which neatly converged on a story that the choice was binary between them. By contrast, the PYD has created a small industry in tours for Western journalists.

The problem, therefore, is not access but accuracy. Much of the coverage that makes its way out of PYD-held areas is emotive and congruent with PYD messaging. This is hardly surprising. The PYD has said that it will treat any information released without its direct permission as “an attempt to deliver information to terrorists”. Inside Rojava, journalists are constantly in the presence of a “minder,” and the PYD holds over all journalists the ability to bar a return visit if journalists produce output that offends the party. When something more critical is presented, as for example by Feras Kilani at the BBC recently, it was met with much abuse, and sinister accusations of being “anti-Kurd” and “pro-IS”.

The covering up of the negative aspects of the party’s governance and its political extremism gives a very distorted picture of the trade-offs involved in making Western policy in Syria.

Whose Ally?

Once the PYD’s nature as a branch of the PKK is understood, its support for the Russian intervention in Syria, its seconding of Russian airstrikes to attack Western-backed rebels, its political courting of Moscow, and its evident close links to the Assad regime (and Iran, which de facto controls Assad) are no longer a mystery.

The PKK was formally founded in 1978 but, nearly destroyed inside Turkey after the September 1980 coup, it was reconstituted in the early 1980s in camps run by the PLO in the Bekaa, then under Assad’s occupation, with Moscow’s direct input—a weapon to be used by the Soviets against NATO member Turkey. In 1984, the PKK launched its war against the Turkish state from bases in northern Iraq and in 1986-7 the PKK secured an alliance with the Iranian revolution that offered more protection than the live-and-let-live deal the PKK had with Saddam Hussein. Moscow’s support to the PKK diminished after the fall of the Soviet Empire, though links remained, and Tehran continued to find the PKK useful. The main artery of support, however, extended from Damascus.

Ocalan was moved out of the Bekaa and he and thousands of his fighters were based in Damascus. Ocalan once denied that there was a Kurdish Question to settle in Syria since all Syrian Kurds were really from Turkey. The Assad regime was quite content to allow Ocalan to recruit Syrian Kurds for a war in Turkey.

The military junta that took power in 1980 brought repression to the Turkish republic on a scale unknown in its modern history. The Generals wrote this authoritarian and self-serving structure into the constitution and formally restored civilian rule in 1983. For average Turks, by the 1990s the repression had reduced; the Kurdish areas remained under military rule as the state sought to suppress the PKK insurgency. It was in this period, 1992-96, that the PKK-Turkey war was at its most savage. The Turkish government was guilty of numerous war crimes, notably forced displacement to try to drain away with PKK’s support base, and a campaign of “disappearances” and extra-judicial assassinations against politicians, activists, and journalists.

The PKK sought to use the government’s heavy-handed and indiscriminate counterinsurgency effort to overcome its political weaknesses—most Kurds continued to identify primarily as Turks and/or with their religion—and in parallel waged a ruthless campaign to weaken the state and discrediting it by demonstrating that it could not protect those who sought its shelter. The PKK assaulted public works projects, burned down medical facilities, and murdered teachers and civil servants. The PKK was especially focused on the Kurds who opposed it, and licensed indiscriminate slaughter against the villages that had members in the state militia, calling them “traitors” and hanging their bodies from trees with money in their mouths.

Human Rights Watch described the PKK’s conduct as amounting to “crimes against humanity,” reporting,

[B]etween 1992 and 1995, the height of the conflict, Ocalan’s PKK is believed to have been responsible for at least 768 extrajudicial executions, mostly of civil servants and teachers, political opponents, off-duty police officers and soldiers, and those deemed by the PKK to be “state supporters”.

In addition, the PKK committed numerous large-scale massacres of civilians, usually against villagers or villages that somehow were connected with the state civil defense “village guard system”. In twenty-five such massacres committed between 1992-1995 … 360 people were killed, including thirty-nine women and seventy-six children. These actions were not committed by rogue units or commanders, but were PKK official policy.

Ocalan did change this policy when it began to have adverse effects on the PKK’s international standing, but the PKK’s criminal conduct never did end. Between 1994 and 1998, the PKK employed sixteen suicide bombers, eleven of them young women and only one of them voluntary. Westerners were caught up in the PKK’s campaign, sometimes kidnapped, sometimes killed, including British citizens, as recently as the mid-2000s. In Europe, the PKK ran—and runs—a vast enterprise of organized criminality, which extorts from diaspora Kurds and trades in weapons, drugs, and humans to fund the terror-insurgency against Turkey.

After Ocalan’s imprisonment—brought about after Turkey threatened Assad with war—and Ocalan’s subsequent orders for the PKK to de-escalate, Damascus reached an accommodation with Ankara and actually did put its support into a state of dormancy. (Assad refocussed his use of terrorism against Coalition forces in Iraq via the Islamic State’s predecessor.) Between 2003 and 2011, the PYD did experience some repression from the Syrian regime. But the link was never broken and the course was quickly reversed.

When the Syrian uprising broke out in 2011, the PYD was widely considered a wing of the Assad government and busied itself attacking anti-Assad Kurdish demonstrators. It is clear that the PKK reached some kind of arrangement with the Assad regime, conceivably via Iran, at this point. Possible avenues for this are Fehman Husayn, who has deep connections with the Assad regime, and Bayik, who is close to Iranian intelligence, specifically the Ministry of Intelligence (VEVAK). The PJAK/PKK insurgency called off its attacks on the Islamic Republic around this time, and PKK cadres moved from northern Iraq and northern Iran into Syria. The PKK served as a useful wedge within the Kurdish community and complicating factor for Turkey, which was—after an initial hesitancy—supporting the Syrian opposition.

Equally suggestive, when the Assad regime withdrew from the Kurdish areas in July 2012 and the PYD took over, it looked much more like a handover than an expulsion. Large stocks of weaponry were left to the PYD by the regime, and the main Kurdish opposition groups who had joined with the Arab opposition to the regime, Tammo’s Future Movement primarily but the Yekiti Party as well, were targeted by the regime, their leaderships and political structures crippled, leaving a vacuum for the PYD to step into. And the handover was by no means a complete, either. Since then, the PYD has acted in de facto alliance with the Assad regime.

As the International Crisis Group explained:

[T]here is little doubt that the PYD is engaging the regime in a conciliatory rather than confrontational manner … Its initially rapid advance was dependent on Damascus’s … 2012 withdrawal from Kurdish areas; this was mutually beneficial, as it freed regime forces to concentrate elsewhere in the north, while the PYD denied Kurdish areas to the armed opposition. … In some cases, the regime apparently has provided material support to the PYD in its fight against opposition armed groups. …

[R]egime forces have maintained a presence in the largest enclaves nominally under the [PYD’s] control, most notably Qamishli and Hasaka. Damascus pulled back most of its security personnel but kept government services under its charge; for example, it continues to pay salaries to state employees and run administrative offices. Far from leaving these functions to the PYD, it has centralised them, giving it an important edge in relations. …

The PYD did not liberate Kurdish areas of Syria: it moved in where the regime receded; most often, it took over the latter’s governance structures and simply relabelled them, rather than generating its own unique model as it claims. Fringe Arab, Syriac and Assyrian leaders are participating, even if they do not adhere to its ideology, as a way to ensure security and access to services for their communities.

Rojava is thus … an instrument that enables the regime to control Kurdish areas. Established in isolation from the society it means to govern, [the PYD] is overburdened by an ideological foundation with which most Syrian Kurds and non-Kurds scarcely identify. Its political architecture enjoys only narrow buy-in beyond the PYD affiliates and co-opted personalities, and … the movement’s popular legitimacy still seems largely a function of the threat [i.e. instability and Jihadi-Salafists encroaching into Kurdish-majority areas.]

The clashes between the PYD and the regime in Hasaka Province have been sporadic and minimal; thus far the regime has not struck at the area with fighter jets and the PYD has made no move to expel the regime’s forces. [Update: on 16 August, clashes erupted between the PYD and the regime in Hasaka City and on 18 August the regime, for the first time, launched airstrikes at PYD positions in the city. On 23 August, a ceasefire was reached that forced the regime’s militias and troops—though not its police or services—out.] The PYD has even publicly conceded that it is coordinating with the Assad regime. Western governments have detected the PYD-regime coordination, and indeed PYD coordination with Russia.

The SDF contains, as major components, Quwwat al-Sanadid, a (Sunni) tribal force that is said to be led by figures connected to the National Defence Forces (NDF), the Iranian-commanded militia that has overtaken the national army, and the Syriac Military Council, which has its own links to Moscow. Ahmed publicly supported the Russian intervention in Syria and claimed that there were no members of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) in Aleppo or Idlib as Moscow battered those groups with airstrikes in the first weeks of its campaign.

This doesn’t make the PYD a proxy of the regime, exactly. It means the PYD is deeply shaped by the connections and outlook of its founding, that in pursuit of its own state-building project the PYD regards the opposition as its greatest enemy, has no desire to see Assad fall, and looks on Russia as an ally.

By emphasizing their view of Assad as the lesser-evil, the PYD gains access to direct Russian military support to remove Western-supported actors that stand in its way. Russia and the PYD also agree on the need to seal the Turkish border to choke off the rebellion, so they have worked in tandem to accomplish it. As Tony Badran has put it: this would leave the Russian-Iranian-underwritten regime zone in the west, a U.S.- and regime coalition-supported PYD zone in the north, and a “Sunni Arab kill zone” in between.

Beyond shared interests, the PYD/PKK’s inclination has been most evident in the statements of its leaders. Cemil Bayik has praised Assad and the Iranian theocracy as the “only” regimes that follow “a somewhat more independent policy [from the West,] which allowed for political, economic, social and cultural differences.” Given the harsh discrimination of both regimes against Kurds and other minorities—and, in Syria’s case, the majority—this is an incredible statement. More recently, Saleh Muslim exculpated Assad for the Ghouta chemical weapons attack, serving no PYD interest with that lie.

It entitles one to ask what the PYD’s actual intentions are in aligning with a West that the PKK has long despised. The argument from Fabrice Balanche that the PYD will use Western support where it can as part of an “overall strategy of cooperating with Russia in order to connect the Kurdish enclaves” is plausible. Beyond Manbij, Balanche contends that the PYD might spurn Western desires that the PYD move on al-Bab, which would complete IS’s expulsion from urban strongholds in Aleppo, and instead the PYD might dash to complete the land-bridge to Efrin by conquering areas north of al-Bab, using Russian assistance if the West balks.

At that point things would get very tricky: the PYD will have surrounded a pocket that includes the Azaz-Marea corridor in the west, containing U.S.-backed rebels that nobody doubts are moderate, and IS in the east. Would the PYD complete its attempt to destroy the Azaz rebels and leave the West no choice but to back it in then destroying IS? The tactic of presenting oneself as the only alternative to IS has been perfected by the regime and Russia, and such polarization is effective. The Russia “trainers” now embedded with the PYD might well pass this along.

Conclusion

Statue of Mahsum Korkmaz (Agit), the first PKK military commander, in PYD-held Hasaka

However localized the focus of the PYD is for now in Syria, the organization remains deeply beholden to its founding ideas and especially practice, which makes it chauvinistic and despotic in the areas it already controls and unconstrained by state boundaries in its ambitions, with a relentless focus on Turkey.

Echoing al-Qaeda in Syria, which claims that its “Jabhat Fatah al-Sham” is not a faction but a part of the population and a platform for unity, Cemil Bayik once wrote of the PKK as “uniting the Kurdish nation behind its banners,” while other Kurdish groups were “nothing but pawns … of the international powers and allies of the USA.” Also like al-Qaeda, the war situation has provided ideal conditions for the PYD to burrow into society and reshape it as an instrument of the group’s advancement.

The PYD currently enjoys the support even of Kurds who oppose it because they need protection. Without the war in Syria, however, the PYD’s Turkey-centric vision is likely to take over and the alienation with Syrian Kurds will intensify, requiring the PYD to increase its internal repression and decreasing the contrast between a stable Rojava and chaos beyond. And that is if the uncritical Western support for the PYD doesn’t lead to another conflict. One short-term version of this conflict is about to play out in Manbij, where the elected council that was overthrown by IS wishes to return, and the PYD wants to install its own military council. The U.S. appears to be siding with the PYD (again).

The creation of a PYD-run statelet is also troublesome for relations within NATO since the fears that such an enclave would be a source of instability and terrorism for Turkey have factual grounding beyond Ankara’s paranoia.

The U.S. is said to be “hope … that constant contact with the Americans will moderate Syrian Kurdish ties to the PKK in favour of the backing of a superpower.” Perhaps. But there is a reality in the here-and-now about what the PYD is and, given the organic integration of the PYD and PKK, detaching one from the other seems very unlikely on any kind of workable timescale.

There is a strong case for supporting the PYD in keeping IS out of Kurdish areas, not least because thanks to the PYD there is no alternative. But that defensive mission is quite different to encouraging the PYD to occupy Arab cities, which ratifies IS’s propaganda that there is a global anti-Sunni conspiracy and allows IS to claim to be the only bulwark the Sunnis have, granting it legitimacy even as it loses territory. The only outcomes in such a scenario are that the PYD remains, inciting hostility, or the PYD leaves; in both cases it gives IS a way back in. Without a legitimate ‘hold’ force, in combination with IS’s method of force-preservation, the PYD displacing IS in Arab areas will ensure only IS’s revival. Similar dynamics mean al-Qaeda gains from the PYD holding Arab areas, too.

Militarily supporting the PYD to hold IS at bay is also different to supporting the PYD per se. It would be much more appropriate to support institutions in Syrian Kurdish areas—pluralism rather than factions. Trying to leverage the immense Coalition support given to the PYD to free-up political space in Rojava would be more efficacious in securing long-term stability than betting on the PYD.

The “Whose Ally?” section has been updated

Reblogged this on YALLA SOURIYA.

LikeLike

ive given you some criticism before but this is your best yet

LikeLike

Pingback: Turkey’s Intervention in Syria Improves the Prospects for Peace | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: One Man’s Terrorist … | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Obituary: Taha Falaha (Abu Muhammad al-Adnani) | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Of Kurds and Compromises in Syria | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The End of the Islamic State by Christmas? | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Life under the Kurdish YPG in Syria | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Al-Qaeda in Syria Denounces America, Claims to Be the Revolution | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Analysis: ‘Signs of Recovery for the Islamic State’ | The Counter Jihad Report

Pingback: PKK and Propaganda | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Repression Increases in the Syrian Kurdish Areas | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The West’s Partners in Syria and the Risks to Turkey | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Media, Democracy, and Terrorism Laws | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Error of Arming the Syrian Kurds | KurDdaily

Pingback: America’s Kurdish Allies in Syria Drift Toward the Regime, Russia, and Iran | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Turkey Continues to Protest the Coalition’s Syrian Kurdish Allies | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Coalition Allies Play Into Islamic State’s Hands | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Islamic State’s Media Apparatus and its New Spokesman | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: A “Syrian Democratic Forces” Defector Speaks About the Role of the PKK and America in Syria | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: How the Islamic State Claims Terrorist Attacks | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Russia Moves in For the Kill in Syria | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Crackdown Continues in Syrian Kurdish Areas | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Viewing the Coalition’s Flawed Anti-Islamic State Strategy From Raqqa’s Frontlines | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Defeating the Islamic State for Good | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Coalition’s Flawed Endgame Strategy for the Islamic State | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The End of the Beginning for the Islamic State in Libya | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Assad Regime Admits to Manipulating the Islamic State | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Liberating Raqqa from the Islamic State | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Signs of Recovery for the Islamic State | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Islamic State Likely To Increase Terrorism Against Turkey | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: What to Expect in Syria in 2017 | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Latest Chapter of Syria’s Media War: A ‘Gay Unit’ Fighting the Islamic State | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Raqqa Doesn’t Want to Be Liberated By the West’s Partners | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Fresh Wave of Repression in the Syrian Kurdish Areas | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Human Rights Abuses in Rojava and the Anti-ISIS War | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Crisis and Opportunity for Turkey and America: The Minbij Dispute | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Outcome Uncertain as American Involvement in Syria Deepens | Kyle Orton's Blog

Pingback: Turkey's Intervention in Syria Improves the Prospects for Peace | Kyle Orton's Blog