By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on April 7, 2014

Kanan Makiya is of that small school of Arab writers—with people like Fouad Ajami, Ali Allawi, and Said Aburish—who write as if Arabs have any agency at all in the decline of their world. The first part of Cruelty and Silence deals with the cruelty of the Arab world in general and the Saddam Hussein regime in particular, especially its conduct in suppressing the Shi’a and Kurdish uprisings that followed the ceasefire in the 1991 Gulf War and the genocidal Anfal campaign against the Kurds, about which this book is perhaps the most comprehensive source. The second part of the book is an indictment of the Arab intelligentsia who almost unanimously sided with Saddam in his sacking of Kuwait, at best keeping silent about this new crime, as they had kept silent about all his others, and directing their energies against those who stood up against Saddam. Twenty years later, this book still serves as an excellent guide to the maladies of the Arab world.

Makiya begins with “George Bush’s unfinished war”. Saddam’s aggression had to be confronted: a world in which small States could be erased is not tenable. Having gotten the Iraqi army out of Kuwait, something extraordinary then happened: hajiz al-khawf inkiser (the barrier of fear was broken). For centuries States have hoped that by bombarding an enemy they can cause their people to rebel and it has never worked; under outside threat people rally to the flag. It tells you everything you need to know about Saddam’s regime that despite watching comrades blown to pieces by Allied bombs, large numbers of Iraqi soldiers—terrified and exhausted, forced to trek across the desert for days—gathered in Basra after being forced out of Kuwait, where they “chose to turn their wrath against the tyrant”.

When the pent-up furies of two decades of totalitarianism boiled over, it was not a merciful affair. Makiya notes that in poring over the evidence of the Shi’a uprising afterward, “I often found myself nauseated, even estranged from an uprising that I had thrown myself into supporting heart and soul while it was going on.” Still, “In extreme circumstances, the obscene and sublime can combine”. The Shi’a took vicious revenge, tearing to pieces the Ba’athist personnel who fell into their grasp. (It is worth bearing this in mind when considering the Syrian rebellion at present: the insurgents have behaved much better—even squeezed between the regime and the takfiris—than the Shi’a did that year, but there are few who doubt that things would have been better if the Shi’a had prevailed over Saddam Hussein.)

The invasion path of Operation Desert Storm, the Allied effort to get Saddam Hussein out of Kuwait. Launched from Saudi Arabia, it tricked the Iraqis with the direct move into western Kuwait, which they were expecting, and the “hook” through the Iraqi desert into northern Kuwait, which they were not.

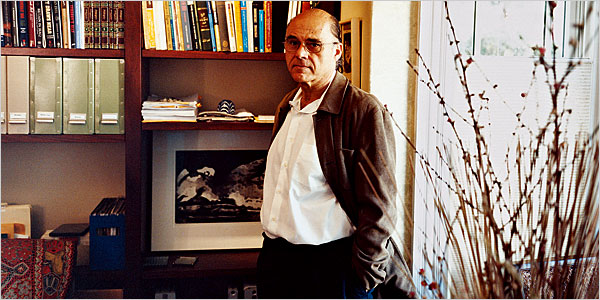

Makiya, who had published the best-selling Republic of Fear under the pseudonym “Samir al-Khalil”, abandoned his anonymity during the uprising, going public on 7 March 1991 to say:

“The scale of Iraqi defeat carries with it a historical opportunity for a new beginning, one likely to shape the region’s politics in less than a generation. But first allied forces must openly recognise and work with the Iraqi insurgents … and march into Baghdad.”

He was not heeded. The Allies did extraordinarily little direct damage to Iraq’s civilians—maybe 3,000 were killed. But the “high-tech character of the war … terminat[ed] Iraq’s existence as a modern state … just hours into its start”. Iraq had been the most developed State in the region in the 1970s; the targeted air strikes destroyed the roads, bridges, sanitation works, and power grids, leading to the collapse of the healthcare system and water-delivery services. Baghdad was like “a body with its skin basically intact, with every main bone broken and with its joints and tendons cut,” said Richard Reid of UNICEF. 90,000 were dead from the failed rebellions; sanctions in place to contain the regime were manipulated by it to repress its opponents further (water was trucked into Basra, for instance, so it could be cut off if the Shi’a dissented again); and disease followed. It left Iraq traumatised, beggared, and ruined. That was the result of pulling up short in 1991.

Makiya’s case for having finished the war is impossible to refute by anybody of any strategic sense or empathy. “The United States was not obligated to come halfway across the world … to sort out the problems of the Middle East,” Makiya writes. “But once the United States chose to shoulder that responsibility … it acquired an obligation to the people of Iraq to end things differently.” Given the nightmare of the Iraqi people in the 1990s—scarcity piled on top of totalitarianism—and the aftermath of finally deposing the regime, it could hardly have been worse to have finished this in 1991.

Those who would taunt Makiya about his support for the 2003 invasion of Iraq should note his prescience. Makiya wrote recently in the New York Times of the way in which the vicious sectarianism now at play in the region, notably in Syria, began in earnest in that fateful month when Saddam Hussein mobilised what remained of his shattered regime to slaughter the Shi’ites by frightening the Sunni Arabs with the spectre of vengeful Shi’ite sectarianism and theocracy. The slogans painted on the Iraqi regime’s tanks read: “No more Shi’as after today”.

Makiya was not only seeing this in hindsight. Spelling out the danger of sectarian war after the regime because of the tensions it deliberately stoked as a means of keeping itself in power, Makiya wrote:

“After Saddam has gone … Sunni fears of what the Shi’as might do to them … are going to become the major force of Iraqi politics. The more Iraq’s Shi’a assert themselves as Shi’a, the greater the tendency of Iraq’s Sunni minority to fight to the bitter end … If Iraq dissolves into even more chaos and bloodshed in the post-Saddam era, it will be principally because Shi’i political leadership failed to rise to this historic occasion and to the responsibilities which its own numbers impose on it.”

Which is more or less exactly what happened. The Shi’a were actually more restrained than might have been expected—though the most Iran-friendly Shi’ite factions did begin liquidating Ba’athists soon after the statue came down (another thing Makiya warned about: “the involvement of Iran in anything to do with Iraqi affairs is the kiss of death”.) But the Shi’ites did eventually accept the challenge of the Sunni provocations and all-but cleansed Baghdad of Sunnis, all while insisting that they were the victims of Ba’athism. In truth, while the Sunni Arabs were primus inter pares, the Ba’ath State was “built on circles of complicity which left no one untouched”, Makiya documents: “everyone acquiesced and compromised with dictatorship.” The 1991 Shi’a rebellion could not have been defeated without Shi’a tribes siding with the regime, and the Anfal campaign could not have happened without the Jahsh, a quarter-million Kurdish militiamen allied to Saddam.

Makiya also foresaw the other major issue: Kurdish separatism. Makiya encouraged the Arabs to accept federalism or independence if the Kurds wanted it: The Kurds had been given a de facto polity of their own by the no-fly zones imposed after the ceasefire and there was no way back from that experience. More important, wrote Makiya, Arab Iraqis should not want there to be a way back from that. Cryptically though it is stated, Makiya was also probably correct that the Iraqis could not have removed the regime on their own. There were no-fly zones, draconian sanctions, coup attempts, and limited airstrikes: none of it moved the regime. Iraqis were searching for hope, Makiya wrote, but, “Alone, we cannot do anything.”

Taimor Abdallah Rokhzai in Nov. 1991 being interviewed by Kanan Makiya, shown in the 1992 TV documentary ‘The Road to Hell’ (shown on PBS in 1993 as ‘Saddam’s Killing Fields’). The only survivor of the Anfal mass-shootings, he was 12 in 1988.

The most harrowing section of the book is about the Anfal campaign, which began in February 1988 and lasted until September, murdering 100,000 Kurdish non-combatants. This was the culmination of a long campaign of ever-escalating deportation and murder against the Kurds stretching back to the Ba’ath’s seizure of power in 1968. Between 1969 and 1974, twelve Kurdish villages were destroyed. By 1979, this totalled 1,189. From 1986 through 1988, just under 2,000 Kurdish villages were eliminated, with 1, 276 villages demolished in the February-September 1988 period alone. In all, 3,500 Kurdish villages were destroyed between 1968 and 1988. Makiya compares this with the 369 Arab villages destroyed by Israel in the War of Independence in 1948, about which the Arab world has never ceased to agitate, yet there was nothing said about Anfal.

In 1976, a border zone with Iran, five-to-ten miles wide, was cleared of Kurds. There was limited compensation in those days, and rehousing, albeit in squalid ghettos. The famous Barzani clan had about 50,000 people resettled in southern Iraq and then moved to a camp outside Erbil in 1981 called Gushtapa. In 1983, the regime rounded up about 8,000 men and boys and took them into the deserts of southern Iraq near the Saudi border. Some of their bodies were discovered in mass-graves after liberation; they had been shot. This was the template for al-Anfal. Though everyone now knows of the chemical weapons attack on Halabja—and Makiya documents such attacks on Shaikh Wisan, Guptapa, and Tuka—these terrorising tactics were a side-show to the “bureaucratically-organised, routinely administered mass-killing of village inhabitants,” which was done with entirely conventional means. In the intelligence files captured by the Kurds during their rebellion, the full truth of what Saddam had done was laid bare, and Makiya interviewed the only known survivor of this Iraqi Babi Yar: Taimor Abdallah Rokhzai, 12-years-old in 1988, who later testified at Saddam’s trial.

The most infamous photograph from the chemical weapons attack on Halabja, a woman who has tried to shield her baby from the poison gas

A mass grave of Kurds found in Muthanna Province in 2005.

There are individual shocking scenes of cruelty. The “civil servant paid a salary to rape Iraqi women,” as shown in the documents captured in Kurdistan, is an outstanding example. It is one thing to know that Iraq was the “first totalitarian state to regularly use rape as a means of political control”; it is something else to see it in cold print, on official documents, that a man’s job is: “Violation of Women’s Honour.” The sexual violence was extraordinary: every prison had a rape room and there was campaign to “break the eyes” of Ba’athist opponents, especially the aristocrats, after seizing power. This was a Tikriti “tradition” that Saddam and his tribal loyalists brought to Baghdad: young women were kidnapped, held for a few weeks, repeatedly raped, and returned home. Everyone knew what had happened; nobody would say anything. Sometimes videos of the event would be sent to the fathers and husbands. In the shame culture of the Arabs, this left these men unable to show their faces in any public way, unable to become vocal opponents of the regime. In short, male relatives who enforced this culture were “as complicit as the Iraqi secret police in the victimisation of the women of Iraq,” and ultimately in the victimisation of all Iraqis since the ease with which the mukhabarat could recruit women via this method made all Iraqis vulnerable.

Makiya’s previous—and probably most famous—book, ‘The Republic of Fear’ (1989), which became virtually required-reading in Washington after Saddam Hussein annexed Kuwait

The most moving scene in the book, and one that helps elucidate how the maladies of the Arab world operate at an individual level, is when Makiya writes of how happy he was to receive a British passport: he was now free of having to go to the Iraqi Embassy in London and posting friends on the corner to check he came out again, and was able to travel without the constant suspicion an Iraqi passport provided. But in the eyes of the Iraqi State, he was now a traitor—he had thought “non-Ba’thi thoughts” in a system that “explicitly associates nationality with private belief.” Worse, most Arabs thought that way too. Many of them, having fled the burning grounds of Islam for the safety of the West, felt they had to maintain a distance from their new homelands. “[A] big lie has to be maintained in the shape of a denial that the change means anything. … Many Arabs enjoy the very benefits that they will then deny they wanted so desperately as they sought to obtain [Western] passports,” Makiya writes. To blame this only on the regimes misses the point: these rulers did not descend from the sky; their regimes are not maintained by them alone.

The final section of the book deals those who have been the most important props of the regimes: the Arab intelligentsia. It deals with some Western intellectuals like Noam Chomsky, who managed to stake out an anti-American position during the 1990-91 Gulf Crisis, even at the expense of being pro-Saddam. Makiya’s admirable insistence on playing the ball rather than the man leads him to omit that Chomsky’s anti-Americanism had earlier led him to running interference for the Khmer Rouge. Makiya credits Chomsky for managing to avoid the foolishness “line” that many Arab intellectuals took of suggesting that Saddam had been trapped by the United States into invading Kuwait so that the Iraqi military machine could be destroyed to shore-up Israel’s position, albeit Chomsky only just managed this. Chomsky believed a “peaceful” settlement should be found to a war that was already underway and proposed allowing Saddam a chunk of Kuwaiti territory so Iraq reached the sea. Having himself written of Saddam’s Iraq that it was “perhaps the most violent and repressive state in the world,” Chomsky now proposed that Saddam had made an essentially reasonable request, and finessed such a daring intellectual thrust with constant references to alleged U.S. foreign policy disasters elsewhere like Vietnam. Chomsky had shown himself unable to “think through the specifics” of what this mean for the Iraqis and Kuwaitis under Saddam’s rule, Makiya writes, and of the consequences for them of Saddam achieving “something that could be palmed off as victory.”

Of the Arab intellectuals, there were those in the region and those in the West, and the latter probably behaved worse—they had access to more information and (worse) many privately confessed to knowing exactly the character of the Saddam regime they defended in public. Edward Said was a salient case of an Arab intellectual in the West, someone indeed whose Orientalism (1978) “influenced a whole generation of … scholars and … shaped the discipline of modern Middle East studies”. But Said’s behaviour—as on so many other occasions—was nothing short of disgraceful. His wretched book “operates through a populist ethos of Arab prejudice” and a “politics of resentment against the West,” which was a disaster coming from “probably the most perfectly situated Arab to” affect Arab opinion. Said’s book did “nothing to reshape Arab stereotypes of the West”—it actually says that “every European” who has written about the Orient is “a racist, an imperialist, and almost totally ethnocentric”—and instead Said’s tome reinforced the ruinous ideas that Arabs “desperately need to unlearn”, Makita argues. Said joined the vast majority of Arab intellectuals in finding ingenious ways of making Saddam’s blatant aggression America’s fault, writing that the U.S. had “almost invited [Saddam] into Kuwait” and cast doubt on it being Saddam who gassed the Kurds for good measure.

The principal reason adduced by Arab intellectuals for letting Saddam get away with grabbing Kuwait or at least being allowed to gain from it was “linkage”: that is, linking the demand that Saddam give up his occupation of Kuwait to the demand that Israel give up her then-occupation of Gaza and the West Bank. The best response came from the 70-year-old Emile Habibi, a Palestinian: “The only linkage that the Palestinians would come out with is the one that ties their cause to the fate of the Iraqi leadership”. Makiya added that “linkage” was self-defeating on its own terms: “The nationalist equation has a terrible reverse logic. Suppose the West were willing to let Iraq have Kuwait. Why wouldn’t it demand ‘compensation’ in the form of permanent Israeli annexation of the West Bank?” The Arab States that many of these intellectuals served had done nothing for the Palestinians, least of all Saddam’s Iraq. Makiya caustically writes:

“Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, and ‘experts’ in Arab politics were immediately convinced that with his ‘Arab’ strength crumbs of comfort were going to be tossed in their direction in the shape of Israeli concessions. This is what the struggle against Israel amounted to in the minds of intellectuals. One didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.”

Arabs had devoted their energies in all the wrong ways:

“[T]his idea that somehow you can build strength in the shape of weapons and forgo the hard task of finding it in the creative productive potential of your own society, has been at the centre of Arab politics for a very long time now.”

How the Arab “street” had thrilled when Saddam threatened to “burn up half of Israel with binary chemical weapons,” believing that this military destruction was the way out of the Arabs’ shame at lagging so obviously—and so far—behind the tiny, besieged Jewish State, never thinking that perhaps something was wrong if 300 million Arabs could not culturally compete with seven million Israelis.

The Arab intellectuals gave a “collective hysterical outburst” during the Gulf Crisis, says Makiya, which revealed their “deepest feelings”. They had spared no rhetorical attack on America for getting Saddam out of Kuwait and had then kept completely silent about the slaughter of the Iraqis who rose up against Saddam. The constant evasions and deflections onto outsiders for what had gone wrong showed the “pathology of a culture”. These dictators, then, “are indigenous creations of modern Arab political culture” and the Arab intellectuals are “overwhelmingly responsible for the deplorable state of their world.” The ideologies—pan-Arabism, Marxism, and Islamism—made little difference. This collective identity, however expressed, is one of “sentiments and traditions,” a “component part of culture, not an explicit political ideology.” In all incarnations, Makiya laments, it ends in a “thought-killing resentment” and a discourse that is “deeply hostile to accepting a notion of individual human rights”. The silence Makiya writes of has been brought about not out of fear but a “poverty of thought”: the constant accusations of double-standards against the West on ideas like democracy and justice have not translated into a sharpening adherence to such principles, but into their abandonment. There has been, in the final analysis, “an implosion, a moral collapse in the Arab world.” In looking for the reasons that the Arabs looked to a theocratic alternative to the nationalism of the 1950s-60s this is a large part of the reason. Why did the women of the Egyptian elite take to veiling themselves? As a means of protest against an order that disgusted them. The mosque was one of the few outlets and, with a political order that rotten, any outlet seemed like salvation.

Makiya’s closing appeal is a simple one: for honesty among Arabs. Arabs must say truthfully what they see and what they know, no matter the use their words can be put to by outsiders. The policy of not airing dirty laundry in front of the West led the Arabs into a dead end of backwardness and despotism. Honesty is the only way out.

Pingback: Film Review: This Is What Winning Looks Like (2013) by Ben Anderson | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Nouri al-Maliki Is Pushing Iraq Into The Abyss | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Book Review: Virual Caliphate (2011) by Yaakov Lappin | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Book Review: Virtual Caliphate (2011) by Yaakov Lappin | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Why The Anti-War Movement Doesn’t Get Off So Lightly From the Disaster in Iraq | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Obituary: Fouad Ajami | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Will The Alawis Break With Assad? | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Iraq Is Still Suffering The Effects Of Saddam Hussein’s Islamist Regime | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Surrendering To North Korea Over ‘The Interview’ Sets (Another) Bad Precedent | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Saddam and the Islamists, Part 2 | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Film Review: Control Room (2004) | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Kamel Sachet and Islamism in Saddam’s Security Forces | The Syrian Intifada