By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on February 5, 2016

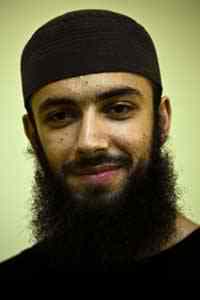

Mirsad Bektašević (2005)

I recently wrote about the jihad in Bosnia. This much-neglected aspect of the war in the 1990s was crucial in shaping al-Qaeda, and global jihadism more broadly, providing this movement, and Clerical Iran, with a staging post in Europe, not least because Tehran’s spy-terrorist capabilities had been deployed to bring many of the jihadists into the country and train them in the first place. While Islamist militancy and terrorism were brought to Bosnia largely as imports, their entry was facilitated by the Party of Democratic Action (SDA), the ruling party to this day. While the war itself trained many jihadist “graduates,” almost all of whom were allowed to stay (or at least received Bosnian passports that gave them that right), the entry of extremist charities/missionaries to lead the rebuilding, many of them bankrolled by Saudi Arabia, entrenched the jihadists and spread their form of Islam in Bosnia after the war. As such, Bosnia became a hospitable operating environment for Islamist recruitment and training and both veterans of the war and people radicalized in Bosnia since have continued to show up in the ranks of international terrorism. It is of interest, therefore, to have an important old case re-emerge in a new way in the last few days, that of Mirsad Bektašević, which again highlighted Bosnia’s importance in the formulation of the infrastructure that underpins the jihadi-Salafist movement, the less-than-clear division between al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (IS) when it comes to the European facilitation networks, and the dangers of seeing Iran as a partner in stability.

Bektašević was born on July 30, 1987, in Sandžak, a predominantly Muslim area of southwestern Serbia, and moved to Sweden in 1994, where he acquired citizenship. Bektašević and another Swedish citizen, named only as al-Hasani Amer, a 20-year-old (or possibly 19) of Yemeni descent, left Sweden about three weeks ago, arriving by plane in Greece and booking a bus ride to Turkey, travelling through Thessaloniki and then Alexandroupolis, where they were arrested on January 28, having almost certainly intended Syria as their final destination, allegedly to join IS. Bektašević and Amer were found in possession of two large knives (machetes by another report), military uniforms, and bulletproof vests. Having initially been picked up the weapons charges, after a tip-off to the Greek government by an allied foreign intelligence agency, Bektašević and his companion were formally charged with “terrorist activity” on February 2. This is not a first for Bektašević, who has been on the radar of European security services since at least 2005.

On October 19, 2005, Bektašević, then only eighteen-years-old, and two other Bosnian citizens, Bajro Ikanović and Almir Bajrić, plus Abdulkadir Cesur, a Turk, were arrested in the Bosnian capital while plotting to blow up the British Embassy, “hiding explosives inside lemons and tennis balls and trying to set up training camps in the hills near Sarajevo.” A fifth person was arrested on November 24 of that year in Hadžići, a town just over ten miles southwest of Sarajevo, “found [with] about 20 pounds of explosives hidden in [the] woods near his home.” While the man’s name was not made public he was “suspected of being in charge of providing explosives to the rest of group.”

Bektašević, who was using the codename Maximus (or Abu Imad as-Sanjaki on some forums), was found to be running a website for Ahmad al-Khalayleh, the infamous founder of IS, better known as Abu Musab az-Zarqawi, whose group in Iraq was then formally part of al-Qaeda. This was at a time when Zarqawi and his acolytes were only just beginning to upload their “virtual caliphate” onto the soil of the Fertile Crescent; then as now the cyber-jihad was important to the Zarqawi’ists.

Bektašević had travelled to Bosnia in September 2005 with Cesur to acquire explosives and the duo were featured in a video demonstrating how to make a bomb and threatening the unbeliever nations. While Bektašević had been radicalized in the West, he found Bosnia as a base, the legacy of the jihad and SDA government. Bektašević was in possession of pictures of the White House on his computer, and it was subsequently deemed plausible (p. 318-19) by Bosnian and British investigators that Bektašević was involved in planning suicide attacks against the White House and the Capitol. Certainly, Bektašević had intended to turn the explosives he had acquired into a suicide vest, according to the indictment.

Bosnia was acting as a facilitation hub for global jihad, because of the networks laid down during the 1990s war, the official complicity in same, and the ongoing rather permissive attitude of the authorities toward jihadist organizing, especially if it was externally directed. Bektašević was in contact with numerous known Islamist terrorists in numerous countries, including one called, unimaginatively, the “terrorist 007” by MI5. The rollup of the Bektašević cell led, on October 27, 2005, to the arrest of four men in Denmark who had been in telephone and email contact with Bektašević and whose terrorist attack against targets in Copenhagen was “imminent,” according to police spokesman Joern Bro. A few days later, in November 2005, three more of Bektašević’s contacts were arrested in Britain.

This came after a spate of Bosnian-linked terrorists had been rounded up on the Continent. In August 2005, Zagreb arrested five Bosnians originally from Gornja Maoča—a veritable Salafist commune in northeastern Bosnia—after Italy had picked up a member of their cell in April and discovered their involvement in a bomb plot against the papal funeral. A month before the arrests in Croatia, Abdelmajid Bouchar, a Moroccan citizen, was arrested in Serbia and extradited to Spain where he was wanted for his role in the March 2004 Madrid bombings. Bouchar was trying to get to Bosnia (or possibly Kosovo), either to hideout or to connect with the jihadist networks that could get him to safe haven in the Middle East.

Bektašević’s 2005 arrest came at a time when Europe was becoming deeply concerned about so-called “White al-Qaeda”. “They want to look European to carry out operations in Europe,” as one Western intelligence agent put it. The extent of Zarqawi’s networks in Europe was beginning to become evident, and it was proving difficult enough to keep track of among known radicals and criminals; the possibility of “cleanskin” converts taking up domestic terrorism was an especially alarming one.

(Zarqawi benefited from the complicity, by omission and commission, of Bashar al-Assad, whose intelligence apparatus helped funnel the foreign fighters from Europe and elsewhere into IS’s predecessor in Iraq. As early as April 2003, Italian investigators uncovered Zarqawi’ite networks operating between Syria and Europe. While Rome stopped short of directly accusing Assad of helping the takfiris, the Italians did point out that “the Syrian government has aggressive security services that would most likely be aware of extremists operating in their territory.”

Zarqawi had, with Assad’s cooperation, set up the “ratlines” that would bring the foreign volunteers to his terrorist group a year before the invasion of Iraq. Zarqawi had been in Baghdad in May 2002 and by mid-2002 had moved into Syria and the Ain al-Hilweh Palestinian camp in southern Lebanon to set up these networks. One of Zarqawi’s recruits in Aleppo was Taha Subhi Falaha, better known as Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, IS’s powerful official spokesman and a rare Syrian in a group mostly led by Iraqis. Zarqawi also benefited from Assadist collaboration (p. 106-107) in assassinating USAID ambassador Laurence Foley in Jordan in October 2002.)

The other dynamic Bektašević’s 2005 apprehension elucidated was that of the extremist missionaries in Bosnia. Bektašević had not been a warrior during the war, but had come in afterwards to live in shari’a-compliant territory and engage in terrorist recruitment and planning. Rather than somebody like Abdelkader Mokhtari (Abu Maali), the legendary Algerian mujahideen commander, Bektašević resembled the “Algerian six,” the cell led by Bensayah Belkacem that was broken up in Sarajevo in the days after 9/11. Belkacem and his comrades had come to Bosnia after the war and took up posts with “Allah’s NGOs,” the web of Islamic “charities,” financed to varying degrees and in various ways by the Saudis, that had once financed Islamist battalions like the Seventh Muslim Brigade and which now engaged in dawa (proselytization) for Wahhabism and other extremist variants of Islam. One thing Bektašević/Belkacem and Mokhtari shared, however, was the endorsement of the Bosnian government, expressed specifically by its practice of naturalizing Islamist radicals. While much of this was done with the estimated 12,000 passports that “went missing” during the war, Mokhtari had received his passport on March 13, 1992—before the war started (p. 320).

Mirsad Bektašević

Bektašević was sentenced to fifteen years and four months in prison in Bosnia on January 10, 2007, but he didn’t serve anything close to that: he was transferred back to Sweden in June 2009 and released on May 10, 2011. Bektašević is also reported to have been arrested for carrying a pistol in 2013. The same report says Bektašević has also been thwarted in separate efforts to return to Bosnia and Serbia since 2011. There is also a claim Bektašević has tried at least once before, in 2014, to travel to Syria—though, interestingly, Bektašević’s social media and other internet footprints suggest that at that time he wanted to join Jabhat an-Nusra, al-Qaeda’s Syrian branch. If Bektašević has now switched his allegiance from Nusra to IS, this would be a well-worn path for foreign jihadists, including Europeans like Mohammed Emwazi (“Jihadi John”). It would also demonstrate again that while IS and al-Qaeda are engaged in total war in Syria, the lines between their networks abroad, notably in the Balkans, are rather blurry.

The ease of movement around Europe and the public allegiance of men like Abdelhamid Abaaoud will remain one of the great what-ifs of the Paris attacks. But the fact that the Greek authorities might well struggle to find legal recourse to remove Bektašević, a veteran jihadist facilitator, from the battlefield evinces again that what Europe really suffers is a political problem, not an intelligence one, and for as long as Europe remains free it is a problem that might well be insoluble, at least as it concerns native-born jihadists like Bektašević.

There are broader lessons from Bosnia, where Bektašević cut his teeth. One is the manner in which the nature of the SDA and Alija Izetbegović were misunderstood or overlooked. The power-wielding circles of the SDA, especially those who created its paramilitary formations, were drawn from an older Islamist cadre, the Young Muslims, which bided its time under the Tito regime before seizing the State in the aftermath of Communism. It is a reminder of what a vanguard can do and of the problems Bosnia will continue to have while such people maintain control of the State apparatus. But the most relevant lesson is Iran.

The revolutionary government in Tehran was effectively made a Western partner in Bosnia. Rather than working with the West or helping to aid stability, Iran infiltrated the Bosnian security sector, created parallel structures that crossed over with official ones and exercised equivalent or greater power, and entrenched its intelligence-terrorist infrastructure, using Bosnia as a launch-pad for terrorism, locally and abroad. If this sounds like Iraq and Syria now, it should.

In 1995, Iran tried to kill the CIA station chief in Sarajevo and was instrumental in liquidating foes of its influence (and others found inconvenient by its host government). Throughout the 1990s, Bosnia was a forward operating base for Iran, inter alia during the wave of assassinations against Iranian émigrés. While Iran’s presence was curtailed somewhat later in the 1990s after NATO occupied Bosnia, Hizballah’s robust presence in the Balkans is hardly a secret and it would be surprising if these networks had no part in the 2012 bombing in Burgas, Bulgaria. The turn to Iran as a stabilizing force in Iraq and Syria is already being conducted at gun-point, and the chances seem minimal that the Iranian beachhead on NATO’s doorstep won’t be used to attack the West. The options for what to do about it are unpleasant: as Bosnia showed, once the Iranians are in, they are very difficult to get out.

Pingback: Profile: First Spokesman of the Islamic State Movement - Kyle Orton's Blog