By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on September 3, 2014

On August 25, Bashar al-Assad’s Foreign Minister, Walid al-Muallem, said: “Syria is ready for co-operation … to fight terrorism.” The week before Assad’s PR guru, Bouthaina Shaaban, told CNN that an “international coalition,” including Russia, China, America, and Europe, should intervene to defeat the “terrorists,” whom she says make up the rebellion in Syria.

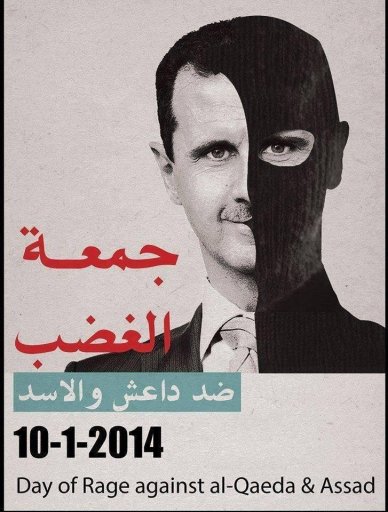

Back in March I wrote a long post laying out the evidence that the Assad regime was deliberately empowering then-ISIS, now the Islamic State (IS), helping it destroy moderate rebels and even Salafist and Salafi-jihadist forces, with the intention of making-good on its propaganda line that the only opposition to the regime came from takfiris, which would frighten the population into taking shelter behind the State, seeing this madness as the only alternative, and would at the very least keep the West from intervening to support the uprising and might even draw the West in to help defeat the insurgency. These statements represent the culmination of that strategy.

At the time of that post, it was rather a minority view to say that Assad was bolstering IS but since then this view seems to have gone mainstream to the point where the French President called Assad “the de facto ally of jihadists.” People struggled to believe a regime could be that canny or cynical; to some it sounded too much like a conspiracy theory. But what Assad has done is not unique.

This tactic is called provocation (provokatsiya in Russian), and “simply means taking control of your enemies in secret and encouraging them to do things that discredit them and help you.” The KGB perfected this tactic, beginning with Operation TRUST, though Russia had invented it under the Tsar. The KGB’s successors have employed provocation in the last few months with the Ukrainian far-Right, which has done so much to discredit the new government in Kyiv; a sanguinary version of this policy was employed by the KGB-trained authorities in Algeria in the 1990s; and it has even been used in democratic countries, such as in America by the FBI against the Ku Klux Klan and the Black Panthers, and in Germany against the far-Right. (Germany is so good at this that the last time the effort to ban the neo-Nazi “National Democratic Party” got to court it was a fiasco because so many of the NDP’s leaders and members were German intelligence agents that it was impossible to say what the group’s true beliefs were.)

The best evidence that something of the kind has happened in Syria, a State where the security apparatus was schooled by the KGB, comes from Bassam Barabandi, a defector from Assad’s Foreign Ministry, who described the regime’s strategy in dealing with the uprising this way:

ISIS’s role in Syria fits into a plan that has worked for Assad on several occasions. When a crisis emerges, Assad pushes his opponents to spend as much time as possible in developing a response. … His favorite diversion is terrorism, because it establishes him as a necessary force to contain it. …

Assad renewed a version of this approach after non-violent protestors took to the streets demanding freedom and reform in 2011. … Assad needed to take steps that would pass time and prove himself as indispensable, both to the international community and to Syrians who fear retaliation from the Sunni majority. …

Assad first changed the narrative … to one of sectarianism, not reform. He then fostered an extremist presence in Syria … [and] facilitated the influx of foreign extremist fighters to threaten stability in the region. … The resulting international paralysis allowed Assad to present himself as an ally in the global war on terror, granting him license to crush civilians with impunity. …

Once the unrest shifted to an armed conflict, Assad’s choice of allies promoted sectarianism. … Today, the conflict has morphed into a sectarian regional proxy war. This is precisely how Assad envisioned it, and creates a dynamic that the internationals can dismiss as too complex or dissonant to Western interests.

The Assad plan also included allowing extremist Sunni groups to grow and travel freely in order to complicate any Western support for his opponents. The Assad regime and Iran have meticulously nurtured the rise of al-Qaeda, and then ISIS, in Syria. … Assad released battle-hardened extremists from the infamous Sednaya prison; extremists with no association to the uprisings. These fighters would go on to lead militant groups such as ISIS and al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al Nusra.

In conjunction with the terrorist-release policy, Assad was sure to imprison diverse, non-violent, and pro-reform activists by the thousands … so that the influence of extremists would fill their absence. Assad was careful to never take any steps to attack ISIS as they grew in power and strength. …

Now that ISIS has fully matured, the Assad regime and Iran offer themselves as partners to the United States. For the first time, Assad is striking ISIS in Raqqa and locations inside Iraq, in a perverse harvest of the terrorist seeds he planted to quash the civilian-led reform movement. Assad will continue to make himself appear helpful by offering intermittent air strikes, details of fighters released from prison, and intelligence. …

The rise of ISIS in Iraq and events in Gaza and Ukraine have placed Assad’s war safely outside the headlines. Once again, the world is convinced it has higher priorities and may again conclude that Assad is a problematic, yet stabilizing dictator in a troubled region.

The Assad regime has perfected the role of being “at once an arsonist and a fireman,” as Fouad Ajami once put it; of creating problems and then exacting concessions from the West to solve them.

The simplest way of demonstrating that the Assad regime wanted to strengthen the Islamic State is to follow the money. IS has essentially five streams of revenue, which are:

- Oil. IS controls the zones where Syria has oil—Raqqa and Deir Ezzor—and has added oil-producing regions of Iraq around Mosul to this. Estimates of daily intake vary between $1m, $1.8m, and $3m, but this is clearly one of IS’s most important revenue streams. It is also agreed by everybody, from our best journalists to the French Foreign Minister, that a not insignificant portion of this comes from the Assad regime buying the oil—handing over millions of dollars to IS that allow it to fund its fighters and military campaigns, and propagate its ideology to the captive population (estimated at between six and eight million people), while letting IS avoid the necessity of looting, a feature of the desperate FSA-branded rebels that has damaged their cause. IS also takes over other resources—notably grain silos in Syria and the wheat fields around Mosul—giving it total control of the population and allowing it to sell the excess.

- Extortion (“Tax”). IS controls some non-Muslim minorities who pay the jizya, which is essentially a protection-racket. Other tribute is drawn as taxes from businesses (in the guise of zakat) and farmers. There are also charges for services like public transport. In total this is thought to bring in $5m per month or $60m per year. The Assad regime has avoided bombing IS-held areas as it does with rebel-held territory, allowing IS to exploit this revenue stream.

- Kidnappings. The U.S. and Britain refuse to pay for the release of their citizens taken hostage but many European States do pay. Some estimates say IS has taken in $65m (£40m) from ransoms. This is plausible. (Al-Qaeda gained $165 over the last six years from European ransom payments.)

- Antiquities. While IS has attracted attention for its obliteration of the region’s cultural heritage, it has a sideline in the sale of artefacts, specifically those looted from Nabuk in Qalamoun, which have given it at least $60m (£36m).

- Foreign Donations. This is the most controversial—and the least important. In the last few months there have been many clumsy accusations that the Gulf States, specifically Qatar, fund IS. So senior a figure as a German Minister said so (and then retracted.) But there is no evidence for this. Qatar is a troublemaker. It funds HAMAS. Ahrar a-Sham, the most extreme Syrian insurgent group, could not exist at its current strength without Qatar’s support. Qatar has also put in place mechanisms that “deniably” allowed resources to reach Jabhat an-Nusra, al-Qaeda’s official Syrian branch, which is foreign-led. Qatar’s role in freeing the Christian nuns in March and U.S. journalist Peter Theo Curtis last week from Nusra also suggest connections. But these groups are at war with IS. When the accusation is levelled at Saudi Arabia, especially by official Qatari sources, it is even less convincing. Kuwait’s banking system has been used to funnel money to the jihadists and even the takfiris, but this is private finance, some of which no doubt does come from Qatar and Saudi Arabia, but Kuwait is cracking down. The truth of it is that the Islamic State is “largely self-funded,” with foreign donations never making up more than five percent of its income even when it controlled far less resources than it does now between 2005 and 2010, and there is “no credible evidence that the Saudi government is financially supporting ISIS.”

There are those who argue that the regime buying oil from IS is merely part of the war economy. This neglects how selective has been the funding, first to Nusra and then IS, and the incredible expense that Iran, which effectively controls the Assad regime now, has gone to in setting up an intricate supply system and in giving free oil to the regime while its supply of saleable oil is (ostensibly) restricted by international sanctions. Further, as IS recently showed, the fractious nature of the tribes in Deir Ezzor mean the regime could have at least tried divide-and-conquer if it wanted to take the oil fields back; instead it allowed a very visible, brutal IS presence to take hold.

The subtlety of the regime’s strategy can be seen by its release of the violent Salafi-jihadists in March, May, and June 2011. Some oppositionists have said that “the majority of the current ISIS leadership” is composed of such people; there are reports that IS’s Emir in Raqqa, Abu Luqman, was one of them. It is not possible to know if this is true. It is, however, possible to say that the largest Salafist rebel groups all had their leaders released from the same cell block in Sednaya: Hassan Abboud (Ahrar a-Sham), Zahran Alloush (Jaysh al-Islam), and Ahmed Abu Issa (Suqour a-Sham). “The regime did not just open the door to the prisons and let these extremists out, it facilitated them in their work, in their creation of armed brigades,” said a defector from the Assadist intelligence services. This was all part of the strategy to push the insurgency in a Salafist direction and heighten sectarian tensions, which “shores up regime support,” creating the kind of environment where a group like IS can thrive. The regime even allowed the killing of minority groups by the takfiris “to convince these minorities to rally around the regime,” as a senior defector put it. “[T]he revolution was peaceful in the beginning so [the regime] had to build an armed Islamic revolt. It was a specific, deliberate plan,” said another former intelligence officer. It doesn’t take the regime being in an “alliance” with IS, let alone the takfiris consciously co-operating with the regime: the regime sets conditions and allows the takfiris to do as they will—on film, for the whole world to see.

There are likely to be infiltrators among the Islamic State’s forces. One IS defector says he knows of mukhabarat agents who “grew long beards and joined” IS. Such agents will be concentrated near the tops of brigades so they can give orders for terrible massacres and displays of barbarity that discredit the whole insurgency, even while essentially every other anti-Assad group is also at war with IS. This was the strategy in Algeria, where the insurgency fell under regime direction. As one DRS defector explained: “During the massacres, the inhabitants of the first houses were deliberately spared to enable survivors say they recognised the Islamists.” That the Assad regime is complicit with jihadist terrorism should not be so difficult to believe: “The Syrian intelligence apparatus has long cultivated ties with these groups … [and] solidified robust logistics networks that facilitate jihadist activity.” The record of Assad’s facilitating jihadists into Iraq to fight for what is now the Islamic State—from Damascus International Airport, no less—is quite plain, as is the shelter given these people inside Syria, before they were let loose on the New Iraq, by Assad’s brother-in-law, the late Assef Shawkat (just google “Abu Ghadiya” or see here.)

Still, these direct tactics are mere addition because for both the Assad regime and IS “their top tactical priority in Syria is identical: destroy the Syrian nationalist opposition to the Assad regime,” as Frederic Hof, the former leader of the Syria desk at Hillary Clinton’s State Department, writes. IS believes itself to be a State authority, the Caliphate reborn, and has always focussed on monopolising power—i.e. destroying the rebels—in liberated areas rather than attacking the regime. The regime, quite reasonably, sees no reason to stop this, so hasn’t, and has even helped: “Towards the centre of [Aleppo] city, the former Isis base … stood unmolested by Syrian jets, just as it had throughout the war. The Tawheed base next door was in ruins.” The regime has annihilated whole cities like Homs and massive sections of Aleppo held by the rebellion because the chaos and killing makes the population yearn for order and even blame the rebels for bringing the violence upon them. The regime has notably not struck the Caliphate’s de facto capital in Raqqa. The regime’s intent to retake control of all of Syria was “likely abandoned by the fall of 2012“. Since then regime military actions especially in the north and east have been about choosing which of Assad’s enemies control the territory; where possible the regime has chosen IS.

The regime’s less-than-full-force approach against IS is now undeniable. Regime supporters have been openly quoted in the New York Times saying Assad doesn’t attack IS as much as the rebels because IS are not so focussed on ousting the regime and their presence helps discredit the rebellion. Izzat Shahbandar, an Assad ally, former Iraqi MP, and close aide to Nouri al-Maliki, who was Baghdad’s liaison to Damascus, said the tyrant told him personally in May that the “strategy [is] to eliminate the FSA”. “[S]ometimes, the army gives them a safe path to allow the Islamic State to attack the FSA and seize their weapons,” Shahbandar said. The end-goal is to be able to ask “the world to help, and the world can’t say no,” Shahbandar concluded. It’s nice when they just come right out with it.

Since the fall of Mosul in June, the regime has started bombing some targets in Raqqa, but an IS jihadist in Raqqa told the New York Times: “Most of the airstrikes have targeted civilians and not ISIS headquarters.” But since the regime “held off from targeting Islamic State … [and] allowed the group to thrive” to that point, it’s difficult to see how it gets any credit for finally doing so, likely at the instruction of Iran because of the threat to Tehran’s ally in Baghdad. (Remember: arsonist and fireman is a difficult job: sometimes the blaze gets out of your control.) The extent of these strikes should not be overstated, and indeed they are essentially an advertisement toward the end-goal of bringing America in on Assad’s side. “The regime wants to show the Americans that it is also capable of striking IS,” explains SOHR‘s director. And the joint regime-IS effort to put an end to the rebellion once and for all in Aleppo goes on. Again, while IS has “facilitated the Assad regime’s advance in Aleppo” by stepping out of its way—and seen the gesture reciprocated—it’s not necessarily a conscious collaboration because the priority for the two is the same: the destruction of the rebels.

One of the beauties of provocation, especially when working with zealots like takfiris or Ukrainian fascists, is that it doesn’t take much to get them to behave in irrational and self-destructive ways; they need only the slightest nudge in one direction or temptation put in their way to drag them in another, and you can get them to do what you want. A recent example of this is the murder of James Foley. There is suggestive evidence that Foley was kidnapped by the regime, yet nobody doubts he was murdered by IS. Assuming the regime did take him, it did not have to do a lot of work to get the entire world talking about what barbarians the “Syrian rebels” are—despite the fact IS is neither Syrian nor, by definition, rebelling against anything: its Iraqi leadership never endured the Assad regime but rather collaborated with it. The savagery of the regime is allowed to fade into the background in this framing, and all it had to do was hand him over; they could trust IS to do the rest.

It might be that people who have followed me this far nonetheless say: “Alright, we agree: it’s largely Assad’s fault IS is such a big problem but IS still is such a problem, and Assad has orchestrated it so there is only the regime and the takfiris to choose from, and we can’t choose the takfiris.” The first problem with this is that it isn’t true: there are moderate (and even Salafi-leaning) rebels with whom we can do business. If the moderates had been able to weaponize their supporters in this fight—a majority of them with military training—the insurgency would not be tilted so heavily in the Islamists’ favour. But just take the Assad piece of this statement, and consider this:

If Assad genuinely wants to fight ISIS today, he is as capable of doing that as [former Iraqi] Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki was … How could the Assad regime fight against ISIS in Raqqa or Deir Ezzor, for example? Would the local population fight side by side with the regime? That is extremely unlikely.

In other words, the Assad regime doesn’t have the capacity for the second part of the provocation strategy: it has built up the takfiris, heavily damaged the moderate opposition, and frightened large sections of the population to its side, but it cannot deal the killer blow to the takfiris. (The evidence that Assad has actually started a serious campaign against IS is also somewhat lacking: as mentioned the airstrikes in Raqqa kill civilians not takfiris.) In short, a counter-terrorism policy in Syria (as in Iraq) relies on moderate Sunnis, and in neither country are moderate Sunnis going to work with sectarian dictatorships underwritten by Iran; the regimes have to go first, then the takfiris can be defeated.

It was quite obvious as soon as Mosul fell that the absolute priority of the West was not being drawn in to Iran’s game in the Fertile Crescent. Iran has been selling itself as a Western ally against the “real” threat, which is, they say, Sunni jihadism. That Iran has thrown maybe 10,000 foreign Shi’ite jihadists into Syria—nearly as many as the Sunnis fighting for IS and Nusra—and is a jihadist regime seeking nuclear weapons recedes from view in this picture. So does Iran’s long record (p. 68; 240-1) of complicity with al-Qaeda and the precursors of the Islamic State. (Indeed Iran was crucial in the formation of IS.) But now we find the U.S. acting as the air force for Iranian proxy groups in Iraq that have murdered hundreds of U.S. and British soldiers and even (in IS-style) hostages. The worst suspicion is that this is not an accident, and is part of the Obama administration’s “preference for partnering with Iranian-backed ‘state institutions’,” a strategy intended to lead to a U.S. rapprochement with Tehran, a balance of power between Iran and the Gulf States (which by definition means empowering Iran), and a U.S. withdrawal from the region. U.S. intervention in Iraq this time around was always fraught with the danger of being Iran’s air force since to fight IS on that side of the border was almost axiomatically to be fighting on the side of a government that had become an instrument of Iranian State power, thus taking sides in a sectarian civil war against the Sunnis who have been disenfranchised to a point that they see IS as a vanguard force. It is also questionable how much interest the U.S. has in rescuing a government that deeply penetrated by Tehran and seconded as a vital pillar of Iran’s regional strategy. These dangers do not exist in Syria: there, damaging IS also damages the Iranian-underwritten regime and helps the moderate Sunnis.

When next Assad is proposed as an counter-terrorism partner, it might be worth pointing out the role he and his masters in Tehran have had in creating the terrorism problem, and how the presence of Iranian-backed killing machines has swelled the ranks of the Salafi-jihadists—and still does.

Pingback: Russia Moves in For the Kill in Syria | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Defeating the Islamic State for Good | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Coalition’s Flawed Endgame Strategy for the Islamic State | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Syrian Regime Helped the Islamic State Murder Americans | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: By Strengthening Iran, the Coalition Has Ensured the Islamic State’s Survival | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Crisis and Opportunity for Turkey and America: The Minbij Dispute | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Syria’s Revolution Has Been Overtaken By Outside Powers | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: HOW SYRIA REVOLUTION TURNED INTO GLOBAL BATTLEFIELD – linesstatic

Pingback: Islamic State Admits to Colluding with Syrian Regime | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Islamic State Admits to Colluding with the Syrian Regime | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Criminality of the Syrian Regime | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Strikes in Syria and America’s Path Forward | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Where Next for the West in Syria? | James Snell

Pingback: A Wave of Assassinations Hits Idlib | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Assad vs. ISIS in Southern Damascus is the Culmination of the Regime’s Strategy | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Syrian Regime’s Funding of the Islamic State | Kyle Orton's Blog

Pingback: The Balkan Front of the Jihad in the Fertile Crescent | Kyle Orton's Blog

Pingback: Iran and Global Terror: From Argentina to the Fertile Crescent | Kyle Orton's Blog

Pingback: Assad and Academics: Disinformation in the Modern Era | Kyle Orton's Blog